Enteric infections

Enteric infections

Enteric infections represent an important burden of illness among Middlesex-London residents, accounting for approximately 11% of all infectious diseases reported between 2005 and 2018. Ongoing health promotion efforts are needed to ensure that progress is sustained where decreased rates have been achieved, as well as to further reduce the burden of other infections and to prevent outbreaks from occurring. These efforts may include ongoing promotion of safer food handling and preparation practices, safe water initiatives, and working with provincial and national partners to advocate for food industry changes that may reduce risks to consumers.

Annual and seasonal variation of enteric infections

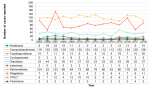

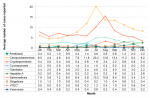

In the 14-year period from 2005 to 2018, campylobacteriosis was the most common enteric infection reported, followed by salmonellosis. Together, reported cases of these two infections were two to four times greater than the number of all other enteric infections combined (Figure 9.3.1).

The average number of enteric infections reported each month varied, ranging from less than one case to more than 20, depending on the disease. In general, the average number of enteric infections reported tended to be highest in the summer months of June, July, and August, with the exceptions of amebiasis, hepatitis A, and shigellosis, for which the greatest numbers of cases were reported in November, October, and February, respectively (Figure 9.3.2).

Interpretation:

For most enteric infections, the average number of cases reported each month peaked in the summer. This increase may be associated with improper food handling practices and poor food temperature control at a time when people are more likely to barbeque and consume meals outdoors.

Amebiasis

View more information about amebiasis.

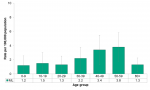

Among Middlesex-London residents, the rate of amebiasis infections generally increased with increasing age, although the differences between age groups were not significant. Rates were highest among those in their 40s and 50s, at 3.4/100,000 and 3.8/100,000 population, respectively (Figure 9.3.3).

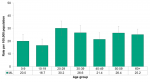

Between 2007 and 2018, the rate of amebiasis infections reported among residents of Middlesex-London decreased from 5.2/100,000 to 2.0/100,000; the Ontario rate showed similar declines. Since 2014, the rate of amebiasis infections among Middlesex-London residents exceeded the rate in the province as a whole, although the difference was significant only in 2015 and 2016 (Figure 9.3.4).

Interpretation:

Prior to 2009, the provincial case definition for amebiasis infections included both probable cases (those for whom the laboratory result detected the parasite but did not differentiate between the pathogenic and non-pathogenic types) and confirmed cases (those for whom the laboratory result detected the pathogenic parasite). This change in case definition may partially account for decreased rates observed both in Ontario and among Middlesex-London residents since that time.

Campylobacteriosis

View more information about campylobacteriosis.

In Middlesex-London, the rate of campylobacteriosis infections was highest among those in their 20s, at 30.2/100,000. In general, the differences between age groups were not significant, with the exception of the rate among 10-19 year olds, which was significantly lower than the rate among those 20-29 years of age (Figure 9.3.5).

Between 2005 and 2018, the rate of campylobacteriosis infections reported among Middlesex-London residents fluctuated between a high of 30.0/100,000 in 2010 to a low of 21.6/100,000 in 2018. By comparison, the rate across Ontario generally decreased during the same time. Across the 14-year time period, the local rate was comparable to the provincial rate (Figure 9.3.6).

Interpretation:

Campylobacteriosis was the most common enteric infection reported among Middlesex-London residents between 2005 and 2018, and the corresponding annual rates were the highest of all reportable enteric diseases.

Cryptosporidiosis

View more information about cryptosporidiosis.

In Middlesex-London, the rate of cryptosporidiosis infections generally decreased with increasing age, from 6.8/100,000 among those under the age of 10 years, to 0.4/100,000 among those 60 years of age and over. The rates among those 0-9 and 10-19 years of age were significantly higher than the rates among 50-59 year olds and those 60 years of age and over (Figure 9.3.7).

The rate of cryptosporidiosis infections increased from 2.3/100,000 in 2005 to 4.1/100,000 in 2018 among Middlesex-London residents. During the same time, the rate in Ontario as a whole also increased. Across the 14-year time period, the local rate was generally lower than the provincial rate; the difference was significant in five of 14 years (Figure 9.3.8).

Interpretation:

Starting in 2018, some Ontario laboratories starting using molecular methods to detect parasitic infections like cryptosporidiosis, rather than microscopic methods. Since molecular methods are better able to detect the causative parasite than traditional methods, the increase in cases observed in 2018 may be partially due to changes in testing methods and better detection.

Cyclosporiasis

View more information about cyclosporiasis.

The rate of cyclosporiasis infections reported among Middlesex-London residents was low, ranging from no cases to 2.4/100,000 depending on the age group. While the rate was highest among those in their 20s, there were no significant differences between age groups (Figure 9.3.9).

Between 2005 and 2018, rates of cyclosporiasis infections were 2.1/100,000 or lower in both Middlesex-London and Ontario, however, both local and provincial rates increased across that time period. In most years the local rate was similar to the provincial rate, except in 2005, 2006 and 2010, when the rate among Middlesex-London residents was significantly lower than the Ontario rate (Figure 9.3.10).

Interpretation:

In 2017 there was a national cyclosporiasis outbreak investigation that included more than 140 cases from Ontario.1 Cases associated with the national outbreak may have partially accounted for the increased rate observed provincially in that year.

In 2018, molecular methods began to be used to detect some parasitic infections like cyclosporiasis. This change in testing method and the associated improvement in detection of the parasite may partially account for the increased local and provincial rates observed in 2018.

Giardiasis

View more information about giardiasis.

Among Middlesex-London residents, the rate of giardiasis infections was highest among those under the age of 10 years, at 10.8/100,000. However, there were no significant differences between age groups (Figure 9.3.11).

Between 2005 and 2018, the rate of giardiasis infections among Middlesex-London residents fluctuated between 4.3/100,000 and 11.3/100,000, depending on the year. At the same time, the rate across Ontario declined. Despite the different patterns, the rate was generally lower among Middlesex-London residents compared to the Ontario rate, and the difference was significant in seven of 14 years (Figure 9.3.12).

Interpretation:

Similar to other parasitic infections, molecular methods have begun to replace microscopic methods for detecting giardiasis. This may partially account for the increases in the local and provincial rates observed in 2018.

Hepatitis A

View more information about hepatitis A.

The rate of hepatitis A infections reported among Middlesex-London residents was highest among those in their 30s (3.7/100,000) and 20s (3.5/100,000). However, there were no significant differences between age groups (Figure 9.3.13).

From 2005 to 2017, the rates of hepatitis A infections in both Middlesex-London and Ontario were 1.7/100,000 or lower, regardless of the year. In 2018, the rate among Middlesex-London residents was significantly higher than all other years in the 14-year time period, at 8.5/100,000, and was also significantly higher than the provincial rate. Similarly, the rate across Ontario as a whole in 2018 was significantly higher than the previous 11 years (Figure 9.3.14).

Interpretation:

Prior to 2017, local and provincial hepatitis A infections were typically associated with travel, or consumption of food contaminated with hepatitis A, such as a 2016 outbreak associated with consumption of frozen berries. In 2017 a provincial outbreak began to emerge, and outbreak cases continued to be identified in 2018 and 2019. Cases in both the local and provincial outbreak were associated with people who use drugs, people who experience homelessness, and to a lesser extent, men who have sex with men. The emergence of the provincial outbreak accounted for the increased rates in both Middlesex-London and Ontario in 2018.

Salmonellosis

View more information about salmonellosis.

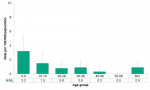

Among Middlesex-London residents, the rate of salmonellosis infections was highest among those under the age of 10 years (28.7/100,000), followed by those in their 20s (28.1/100,000). The rates among these two age groups were significantly higher than the rates among all age groups 30 years of age and over (Figure 9.3.15).

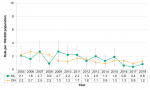

Both the local and provincial rates of salmonellosis infections fluctuated between 2005 and 2018. Among Middlesex-London residents, rates of salmonellosis infections ranged from 11.4/100,000 to 34.6/100,000, depending on the year. In general, the local rate was similar to or lower than the provincial rate except in 2007, when the Middlesex-London rate was significantly higher than the Ontario rate (Figure 9.3.16).

Interpretation:

Across the 14-year time period, numerous local and provincial salmonellosis outbreak investigations occurred, which partially accounted for increased rates observed in Middlesex-London and/or Ontario in those years. For example, provincial outbreaks associated with bean sprouts, frozen breaded chicken products, and chicken products occurred in 2005, 2016, and 2018, respectively. Locally, there were also community outbreaks investigated in 2007, 2016, and 2018.

Shigellosis

View more information about shigellosis.

The rate of shigellosis infections among Middlesex-London residents was highest among those in their 20s (3.0/100,000). The rate among those 40-49 years old (0.3/100,000) was significantly lower than the rate among those 20-29 years of age; this was the only significant difference among all age groups (Figure 9.3.17).

Between 2005 and 2018, the rate of shigellosis infections among Middlesex-London residents was low, varying between 0.4/100,000 and 2.2/100,000 depending on the year. At the provincial level, the rate generally increased between 2006 and 2018. The local rate was comparable to the provincial rate in all years except in 2011 and 2012, when the rate among Middlesex-London residents was significantly lower than the rate for Ontario as a whole (Figure 9.3.18).

Interpretation:

The incidence of shigellosis infections was low among Middlesex-London residents between 2005 and 2018.

Verotoxin-producing E.coli

View more information about verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC).

The rate of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) (E. coli) infections was highest among Middlesex-London residents under the age of 10 years, at 3.2/100,000, and generally decreased with increasing age. However, there were no significant differences among any age groups (Figure 9.3.19).

Between 2005 and 2018, the rate of VTEC infections among Middlesex-London residents fluctuated between 2.7/100,000 in 2009 to 0.4/100,000 in 2017. The rate for Ontario as a whole demonstrated a general decreasing pattern for the same time period. Across the 14-year time period, the rate among Middlesex-London residents was comparable to the Ontario rate, except in 2008, when the local rate was significantly lower than the provincial rate (Figure 9.3.20).

Interpretation:

While the Health Protection and Promotion Act requires that all VTEC cases be reported to public health, Ontario laboratories usually test for only one type of the bacterium, the O157 serotype. As such, the rates reported likely underrepresent the true occurrence of VTEC, as non-O157 types are, for the most part, not included.

Yersiniosis

View more information about yersiniosis.

Among Middlesex-London residents, the rate of yersiniosis infections was highest among those 10-19 years of age (1.9/100,000). However, the differences between age groups were not significant (Figure 9.3.21).

From 2005 to 2018, the rate of yersiniosis infections among Middlesex-London residents was low, ranging between no cases and 1.1/100,000, depending on the year. Across the 14-year time period, the local rate was lower than the rate across Ontario, and the difference was significant in eight of 14 years (Figure 9.3.22).

Interpretation:

Between 2005 and 2018, the incidence of yersiniosis infections was low among Middlesex-London residents.

Other enteric infections

View more information about botulism, cholera, listeriosis, paralytic shellfish poisoning, paratyphoid fever, or typhoid fever.

Between 2005 and 2018, there were no cases of botulism, cholera, or paralytic shellfish poisoning reported among Middlesex-London residents. The total number of cases of paratyphoid fever and typhoid fever in Middlesex-London was also low, corresponding to a rate of 0.1/100,000 for each across the 14-year time period (Figure 9.3.23).

During the same time period, the rate of listeriosis infections among Middlesex-London residents was 0.4/100,000. The greatest number of cases was reported in 2008; in that year, the rate among Middlesex-London residents was 1.1/100,000 (data not shown).

Interpretation:

There was a widespread national outbreak of listeriosis in 2008 associated with consumption of deli meats, which largely accounted for the increased rate of listeriosis cases among Middlesex-London residents in that year. There was a provincial outbreak of listeriosis in 2015 and 2016 involving pasteurized chocolate milk, however, that outbreak did not appear to increase the number of listeriosis cases reported locally.

The variability in the number of enteric infections reported each year and the corresponding fluctuation in reported rates may be due to a number of reasons. For some diseases, increased numbers of cases in a given year may be associated with outbreak investigations. For example, there have been numerous local, provincial, and national salmonellosis outbreak investigations between 2005 and 2018. Changes in testing methods may also account for increases in enteric infection detections. The laboratory methods used in 2005 to detect enteric bacteria (e.g., salmonella, verotoxin-producing E. coli), including phage typing and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), were replaced by 2018 with whole genome sequencing (WGS). Molecular methods have also begun to replace microscopic methods for detecting parasitic infections (e.g., amebiasis, giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, cyclosporiasis), which may have contributed to increased numbers of cases reported in recent years. Finally, across the 14-year time period, provincial case definitions have been reviewed and updated. Increases and decreases in the number of cases reported may be associated with changes over time in the provincial case definition.

For several enteric infections, including cryptosporidiosis, giardiasis, salmonellosis, and VTEC, rates among Middlesex-London residents were highest among children under the age of 10 years. It is possible that children in this age group were exposed more often or were more susceptible to these infections, and therefore the burden of illness in this age group was truly greater than in other age groups. However, it is also possible that parents and caregivers were more likely to seek medical attention for young children compared to older age groups who experienced similar symptoms. Further, health care providers might be more likely to test younger children. Both these factors could contribute to increased detection of infections in children under the age of 10 years for some enteric diseases.

Infectious Diseases Protocol, 2018

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

References:

1. Public Health Agency of Canada [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; [modified 2019 Jun 17]. Public health notice – outbreak of Cyclospora infections under investigation; [modified 2017 Sep 15; cited 31 May 2019]; [about 23 screens]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/public-health-notices/20...

Last modified on: July 26, 2019

Jargon Explained

Enteric infections

Enteric infections effect the intestines and stomach. People with an enteric infection may experience diarrhea, vomiting, stomach cramps, nausea, or other symptoms, depending on the cause of the infection.