Infections prevented by routine immunization

Infections prevented by routine immunization

Approximately 2% of all infectious diseases reported in Middlesex-London between 2005 and 2018 were potentially prevented by immunization. Although immunization programs are well established and, as a result, many vaccine preventable diseases are rare, some infections continue to circulate, such as pertussis. Others infections, like measles, are re-emerging in Canada1 and may pose a risk for re-introduction in the Middlesex-London region as well. Collaboration with health care providers is needed to ensure that population-level protection from vaccine preventable diseases is maintained through routine immunizations, and that if these infections occur, cases are promptly diagnosed and reported to Ontario public health units.

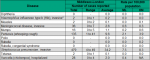

| Infections potentially prevented by immunization | |

| Pertussis |

Infections potentially prevented by immunization

View more information about diphtheria, Haemophilus influenzae type b, measles, invasive meningococcal disease, mumps, polio, rubella and congenital rubella syndrome, tetanus, and varicella.

Between 2005 and 2018 there were no cases of diphtheria, polio, rubella, or congenital rubella syndrome reported among Middlesex-London residents. Invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b, measles, and tetanus infections were rare, with only two cases reported for each in the 14-year time period. Cases of invasive meningococcal disease and mumps were reported, but the rate for each was low at 0.6/100,000 and 0.2/100,000, respectively. During the same frame, the rate of serious varicella (chickenpox) infections requiring hospitalization was also low, at 0.4/100,000 (Figure 9.4.1).

Interpretation:

Among Middlesex-London residents, most vaccine preventable diseases were rare or were characterized by low incidence between 2005 and 2018.

Pertussis

View more information about pertussis (whooping cough).

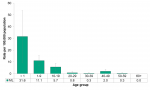

Among Middlesex-London residents, the rate of pertussis infections was highest among infants less than one year of age, at 31.6/100,000, followed by children 1-9 years old (11.1/100,000). While pertussis rates generally decreased with increasing age, there was a small rise in the rate observed among those in their 40s (2.0/100,000), however, it was significantly lower than the rates among the youngest two age groups (Figure 9.4.2).

Between 2005 and 2018, the rate of pertussis infections among Middlesex-London residents ranged between 0.2/100,000 to 9.0/100,000 depending on the year. The Ontario rate also fluctuated during the same time. Across the 14-year time period, the local rate was significantly lower than the provincial rate in seven years, however, since 2015 the Middlesex-London rate has been comparable to the rate for Ontario as a whole (Figure 9.4.3).

In both Middlesex-London and Ontario, 2012 was characterized by a noticeable increase in the rate of pertussis infections (9.0/100,000 and 6.2/100,000, respectively). Smaller peaks occurred in 2015 and 2017 among Middlesex-London residents (3.6/100,000 and 4.3/100,000, respectively) (Figure 9.4.3).

Interpretation:

Beginning late 2011 and extending into 2012, Ontario experienced a widespread pertussis outbreak.2 The outbreak began in an under-immunized community in southwestern Ontario and eventually spread to residents of several other public health jurisdictions2, including Middlesex-London. The peak of pertussis cases observed in 2012 among Middlesex-London residents and Ontario was largely associated with this outbreak.

Pertussis infections tend to increase in a cyclical pattern every two to five years.3 This may have contributed to increased rates of pertussis infections among Middlesex-London residents in 2015 and 2017.

Even with a completed primary immunization series that included pertussis, protection against the infection can wane, anywhere from four to 12 years after vaccination.4 This may also contribute to pertussis continuing to circulate in Ontario.

Although numerous pertussis infections were reported between 2005 and 2018, these case counts underestimate the true occurrence of the disease. Adults who have pertussis may not seek medical attention for their symptoms; the health care providers of those who did seek medical care may not have tested for pertussis. As pertussis can be spread for several weeks, untreated infections pose a risk to people who are un- or under-immunized, including infants who may not have started or completed their routine immunizations.

Invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae

View more information about invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae.

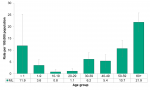

At 21.9/100,000, the rate of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections was highest among Middlesex-London residents 60 years of age and over. The rate among this age group was significantly higher than the rate for all other age groups except among infants less than one year of age (11.9/100,000) (Figure 9.4.4).

Among Middlesex-London residents, the rate of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections varied between 0.9/100,000 and 10.8/100,000 from 2005 to 2018. At the same time, the rate in Ontario increased somewhat, to 9.0/100,000 in 2018. The local rate was comparable to the provincial rate in all years except 2007 and 2008, when the Middlesex-London rate was significantly lower than the rate for Ontario as a whole (Figure 9.4.5).

Interpretation:

There are several different subtypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae, only some of which are components of vaccines administered during childhood or adulthood. The data presented include all subtypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Infections Diseases Protocol, 2018

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

References:

1. Brown C. Measles resurgence comes to Canada. CMAJ [Internet]. 2019 Mar 18 [cited 2019 May 30];191(11):E319. Available from: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/191/11/E319.full.pdf doi:10.1503/cmaj.109-5724

2. Deeks SL, Lim GH, Walton R, Fediurek J, Lam F, Walker C, Walters J, Crowcroft NS. Outbreak report: prolonged pertussis outbreak in Ontario originating in an under-immunized religious community. Can Commun Dis Rep [Internet]. 2014 Feb 7 [cited 2019 May 30];40(3):42–9. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/reports-publications/can...

3. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian immunization guide [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; [modified 2018 Jan 24]. Part 4, Active vaccines, [chapter], pertussis vaccine; [cited 2019 May 30]; [about 25 screens]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-liv...

4. Wendelboe AM, Van Rie A, Salmaso S, Englund JA. Duration of immunity against pertussis after natural infection or vaccination. Pediatr Infect Dis J [Internet]. 2005 May [cited 2019 May 30];24(5 Suppl):S58-61. Available from: https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=15876927 doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000160914.59160.41

Last modified on: July 26, 2019

Jargon Explained

Vaccine preventable diseases

Many illnesses that used to be considered common, such as measles and pertussis (whooping cough), can be prevented by routine immunization. These infections are often referred to as vaccine preventable diseases.