Tobacco

Tobacco

Public Health is responsible for implementing and enforcing The Smoke Free Ontario Act, 2017 (SFOA, 2017), including preventing tobacco use initiation, promoting quitting, limiting exposure to tobacco use and second-hand smoke, and addressing disparities among different population groups.1 One in five adults in Middlesex-London were current smokers in 2015/16, most of whom smoked daily. Adults aged 20 to 44, the urban population and those in the lowest education and income categories had the highest rates of current smoking. About one-third of current smokers had tried to quit for 24 hours in the year prior to being asked in a survey in 2013/14, but trends indicate that the proportion with intention to quit has gone down over time. People continue to be exposed to second hand smoke in their homes, vehicles and public places.

| Smoking Status | Intentions to Quit Smoking |

| Smoking Abstinence | Exposure to Second Hand Smoke |

Smoking Status

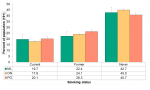

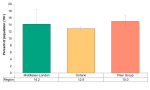

Just under 20% of adults aged 19 years and over in Middlesex-London reported that they were current smokers in 2015/16. Compared to the Peer Group, Middlesex-London had a similar proportion of current, former and never smokers (Figure 5.1.1).

The proportion of daily smokers was 14.2% in Middlesex-London in 2015/16, which was not different than Ontario or the Peer Group (Figure 5.1.2).

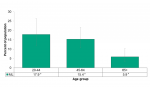

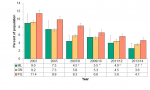

The proportion of those aged 20–44 who were daily smokers was 17.9% in Middlesex-London. This was the age group with the highest rate of daily smoking. The rate in the 45–64 age group was 15.4%. Both the 20–44 and 45–64 populations had rates that were significantly higher than the 65+ population (Figure 5.1.3).

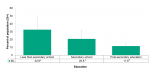

As education level increases the proportion of people who were current smokers decreased. Those with less than a secondary school diploma had a significantly higher proportion of people who smoked daily (32.6%) compared to the proportion of people who smoked daily with a post secondary education (11.6%) (Figure 5.1.4).

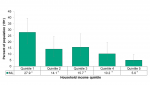

There is also a trend of decreased daily smoking rates as income level increased. Those in the lowest income quintile showed a rate of 27.9% for daily smoking compared to 5.0% for those in the highest income quintile (Figure 5.1.5).

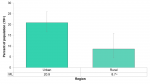

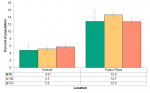

Urban populations (20.9%) had more than twice the rate of current smoking compared to rural populations (8.7%) in Middlesex-London in 2015/16. A similar relationship was seen with daily smoking rates but the rates were too unstable to be reported (Figure 5.1.6).

Interpretation

Current smoking rates were higher in lower socioeconomic groups in Middlesex-London. This relationship is not unique to Middlesex-London. A large meta-analysis, which is a study that combines the data of many other studies to strengthen its results, indicated that those in the lowest income level had a significantly higher risk of being a current smoker. As income increased, the risk of current smoking significantly decreased, indicating a gradient from lowest to highest income levels.2 In another study those with lower education levels were more likely to be current smokers and less likely to intend to quit.3

While this section does not report on the use of vapour products, it is acknowledged that this is a growing issue that will be addressed when data becomes available in the future.

Smoking Abstinence

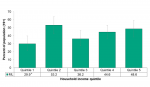

Those in the lowest household income quintile (29.9%) had a significantly lower rate of smoking abstinence than the highest income quintile with a rate of lifetime abstinence of 48.6% (Figure 5.1.7).

Over 98% of the youth population between the ages of 12–17 in Middlesex-London reported completely abstaining from cigarettes in their lifetime. This rate was significantly higher than the Ontario rates (94.5%). Due to small sample sizes socioeconomic factors such as income and education could not be examined for youth abstinence.

Intentions to Quit Smoking

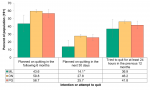

In 2013/14, 43.6% of the population of current smokers, both daily and occasional, indicated that they planned on quitting in the six months following the survey and 13.7% said they planned on quitting in the next 30 days (Figure 5.1.8). The proportion that said they were planning to quit was significantly lower than the province. The proportion of those who said they planned on quitting in the following six months dropped substantially from 65.5% in 2007/8 (not shown).

36.7% of the population of Middlesex-London reported that they had tried to quit smoking for at least 24 hours in the year prior to being asked in a survey in 2013/14. This was a significant drop from 45.6% in 2007/8 (not shown).

Interpretation

Intention to quit is a very important predictor of success and declining rates of those who intend to quit are worth noting. Research suggests that the number of quit attempts may be as high as 30 before successfully quitting smoking; the range indicates that the number of quit attempts for any one individual could be much higher.4 Factors that predicted intention to quit were a greater number of quit attempts and a history of lung disease. Nicotine dependence had an inverse relationship with intention to quit, meaning those with higher nicotine dependence were less likely to intend to quit.5

Exposure to Second Hand Smoke

In 2013/14, 2.7% of non-smoking people in Middlesex-London reported being exposed to second-hand smoke in the home. The proportion of people being exposed to second-hand smoke in the home in 2013/14 was significantly lower in Middlesex-London compared to the Peer Group (Figure 5.1.9).

A significant downward trend in exposure to second-hand smoke in the home was seen between 2003 and 2013/14 in Middlesex-London, the Peer Group and Ontario (Figure 5.1.9).

Almost 5% of people aged 12 and over in Middlesex-London reported being exposed to second-hand smoke in a vehicle in 2013/14 (Figure 5.1.10). This is a decrease compared to 2009/10, but not statistically significant (not shown).

Exposure to second-hand smoke in a public place such as bars, restaurants, shopping malls, arenas, bingo halls or bowling alleys was reported by 12.9% of the population in Middlesex-London in 2013/14 (Figure 5.1.10).

When comparing exposure to second-hand smoke in vehicles or public places in Middlesex-London to the Peer Group and Ontario, no significant differences were found (Figure 5.1.10).

Interpretation

The SFOA, 2017 prescribes where the smoking of tobacco or cannabis, and the vaping of any substance are banned in Ontario. Specifically, it outlines that one cannot smoke or vape in any enclosed workplace or public place, as well as many other outdoor places that are designated as smoke and vapour-free.1 Understanding the proportion of the population who are exposed to second-hand smoke provides valuable information about those at risk from the harms of tobacco use in the context of this legislation.

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

References:

1. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Government of Ontario, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; c2012-2019. Where you can’t smoke or vape in Ontario; 2018 Oct 24 [modified 2019 Feb 20; cited 2019 Mar 27]; [about 8 screens]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/where-you-cant-smoke-or-vape-ontario

2. Casetta B, Videla AJ, Bardach A, Morello P, Soto N, Lee K, Camacho PA, Moquillaza RV, Ciapponi A. Association between cigarette smoking prevalence and income level: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nicotine Tob Res [Internet]. 2017 Nov 7 [cited 2019 Mar 25];19(12):1401–7. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ntr/article-abstract/19/12/1401/2333941?redirec...

3. Corsi DJ, Lear SA, Chow CK, Subramanian SV, Boyle MH, Teo KK. Socioeconomic and geographic patterning of smoking behaviour in Canada: a cross-sectional multilevel analysis. PLoS One [Internet]. 2013 Feb [cited 2019 Mar 25];8(2):e57646 [about 11 p.]. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0057646

4. Chaiton M, Diemert L, Cohen JE, Bondy SJ, Selby P, Philipneri A, Schwartz R. Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers. BMJ Open [Internet]. 2016 Jun 9 [cited 2019 Mar 25];6(6):e011045 [about 9 p.]. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/6/e011045.full.pdf

5. Marques-Vidal P, Melich-Cerveira J, Paccaud F, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Cornuz J. Prevalence and factors associated with difficulty and intention to quit smoking in Switzerland. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2011 Apr [cited 2019 Mar 25];11:Article 227 [about 9 p.]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3095559/

6. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; c2019. Nicotine Dependence [cited 2019 Apr 25]; [About 8 screens]. Available from: https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/mental-illness-and-addiction-index/ni...

Last modified on: May 7, 2019

Jargon Explained

Current Smoker

Smokes cigarettes at the present time, including daily and occasionally.

Former Smoking

Does not smoke at current time but has smoked 100 or more cigarettes in lifetime.

Lifetime Abstainer

Has never smoked a whole cigarette in lifetime.

Nicotine Dependence

Nicotine produces feelings of pleasure, alertness and other mood-altering effects. These physical and psychological factors make it difficult to stop using tobacco, even if the person wants to quit. It is also referred to as an addiction to tobacco.6