Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) were the most common infectious diseases reported in Middlesex-London between 2005 and 2018, accounting for 73% of all cases.

Between 2005 and 2018 the number and rates of all STBBIs reported among Middlesex-London residents consistently increased, regardless of the specific infection. While health promotion efforts are well established and publicly funded treatment programs exist, improvements are still needed in the Middlesex-London region to decrease the burden of STBBIs in our community. Target populations may include youth and young adults, men who have sex with men, and people who inject drugs.

| Annual variation of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections | |

| Chlamydia | Syphilis |

| Gonorrhea | Other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections |

| Hepatitis C |

Annual variation of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

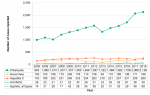

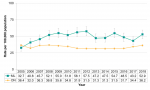

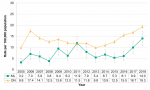

Between 2005 and 2018, the number of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) consistently increased, regardless of the specific bacterium or virus. Chlamydia infections were by far the most numerous, and were two to four times greater than the number of all other STBBIs combined, depending on the year. Although case counts were relatively low, syphilis infections increased nearly five-fold across the 14-year time period, which was the greatest increase among all STBBIs (Figure 9.1.1).

Interpretation:

Year-over-year increases in the number of STBBIs existed despite ongoing health promotion efforts and the availability of publicly funded treatment programs. Further efforts are required to better understand the specific risk behaviours associated with each STBBI, and to address these in collaboration with health care providers and other community partners.

Chlamydia

View more information about chlamydia.

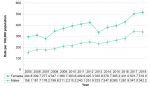

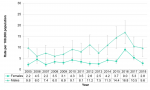

Between 2005 and 2018, the rate of chlamydia infections significantly increased among both female and male residents of Middlesex-London. The rate among females was significantly higher than males across all years. For females, the rate went from 294.8/100,000 in 2005 to 518.0/100,000 in 2018. The rate among males more than doubled in the 14-year time frame, from 156.1/100,000 to 342.2/100,000 (Figure 9.1.2).

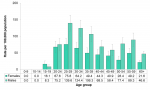

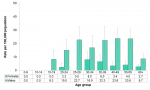

Rates of chlamydia infections were very high among youth and young adults in Middlesex-London. Those 20-24 years of age had the highest rates, exceeding 1,500/1000,000 for both females (2,714.9/100,000) and males (1,560.6/100,000) in this age group. Overall, the 15-19, 20-24 and 25-29 year-old age groups were characterized by the highest rates of chlamydia infections among both females and males (Figure 9.1.3).

The rate of chlamydia infections significantly increased among Middlesex-London residents and across Ontario, nearly doubling between 2005 and 2018. In all years, the local rate was significantly higher than the provincial rate (Figure 9.1.4).

Interpretation:

Despite the very high rates of chlamydia infections reported among Middlesex-London residents, the rates underestimate the true burden of this disease because many people infected with chlamydia have no obvious symptoms, and therefore do not seek medical attention or testing.

Higher rates of chlamydia infections observed among females compared to males likely reflects differing STBBI screening and testing opportunities, rather than a true difference. Sexually active females without symptoms of a chlamydia infection may seek health care for reproductive health reasons, and may be tested for STBBIs at the same time. In contrast, sexually active males may be tested only if they experience symptoms of an STBBI.

Gonorrhea

View more information about gonorrhea.

From 2005 to 2013, the rate of gonorrhea infections was comparable between females and males, and generally decreased. Since 2014, the rate among males has been significantly higher than the rate among females, and increased from 34.3/100,000 to 50.2/100,000. In the same time period, the rate among females more than doubled, from 13.4/100,000 in 2014 to 30.7/100,000 in 2018 (Figure 9.1.5).

For both females and males, the highest rate of gonorrhea infections was among those 20-24 years of age (94.7/100,000 and 126.8/100,000, respectively). Beyond that age group, rates decreased with increasing age, and rates among males were consistently significantly higher than among females (Figure 9.1.6).

From 2005 to 2013 the rate of gonorrhea infections among Middlesex-London residents generally decreased, from 35.4/100,000 to 18.2/100,000. Since 2013, the local rate of gonorrhea infections has consistently increased, more than doubling to 40.5/100,000 in 2018. Across the entire 14-year time period, the Ontario rate increased significantly to 72.2/100,000 in 2018. From 2005 to 2010, the local rate was significantly higher than the provincial rate; since 2011, the rate among Middlesex-London residents has been significantly lower than the rate across Ontario (Figure 9.1.7).

Interpretation:

Increases in both the local and provincial rates of gonorrhea infections may be due to several factors. In Canada and across the world, the bacterium causing gonorrhea is becoming increasingly resistant to the antibiotics used to treat the infection.1 As well, since 2014, the rate among males has been significantly higher than among females. Many male cases were among men who have sex with men (data not shown). This shifting profile may also account for increasing local and provincial rates of gonorrhea infections.

The rates of gonorrhea infections reported among Middlesex-London residents likely underestimate the true burden of this disease in the community. Many people infected with gonorrhea have no symptoms, and therefore do not seek medical attention and are not tested.

Hepatitis C

View more information about hepatitis C.

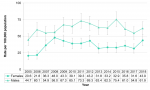

Among Middlesex-London residents, the rate of hepatitis C infections was significantly higher among males than females in all but two years between 2005 and 2018. During this time period, the rate among females more than doubled, from 20.6/100,000 in 2005 to 43.9/100,000 in 2018. For males, the rate increased from 44.7/100,000 to 61.9/100,000 (Figure 9.1.8).

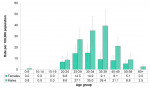

For both females and males, the rate of hepatitis C infections was highest among those 25-29 years of age (75.8/100,000 and 139.6/100,000, respectively). However, in that age group, as well as the 30-34 and 35-39 year-old age groups, the rate among males was significantly higher than among females. Significant differences between males and females also existed in all age groups 50 years of age and over (Figure 9.1.9).

Since 2006, the rate of hepatitis C infections among Middlesex-London residents has been significantly higher than the rate in Ontario as a whole. Between 2005 and 2018 the provincial rate was relatively stable, while the local rate increased from 32.7/100,000 to 52.9/100,000 (Figure 9.1.10).

Interpretation:

Middlesex-London has a relatively large community of people who inject drugs (PWID). Historic studies have suggested that used needles and other drug equipment may be borrowed or lent2, despite robust local needle distribution initiatives. This may contribute to hepatitis C transmission within this community, and may also partially account for the local rate of hepatitis C infections being higher than the provincial rate.

According to the provincial case definition, a newly diagnosed case of hepatitis C is confirmed by a positive antibody test where no previously positive result is available. This includes individuals with newly acquired infections as well as those who were previously infected but newly diagnosed. Starting in 2018, new laboratory methods allowed new infections to be differentiated from previously acquired infections. However, both continue to be considered confirmed cases. Including both new and previously acquired infections may overestimate the rate of new hepatitis C infections.

HIV and AIDS

View more information about HIV and AIDS.

Between 2005 and 2018, the rate of Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) infections reported among males consistently exceeded the rate among females. Since 2012, the difference has been significant in all years but one (2017). From 2005 to 2016, the rate among females significantly increased, more than quadrupling from 2.2/100,000 to 9.0/100,000. The increase among males during that time period was also significant, from 9.8/100,000 to 16.8/100,000. Since peaking in 2016, HIV/AIDS rates among both males and females have decreased in both 2017 and 2018 (Figure 9.1.11).

Among females, the rate of HIV/AIDS infections was highest among those 30-34 years of age (14.9/100/000) and those 25-29 years old (14.5/100,000). For males, the rate of HIV/AIDS infections was highest among 35-39 year-olds (39.4/100,000) and 30-34 year-olds (35.0/100,000). The male rate was significantly higher than the female rate in both the 35-39 and 40-49 year-old age groups (Figure 9.1.12).

From 2005 to 2014, the rate of HIV/AIDS infections reported among Middlesex-London residents was lower than or comparable to the Ontario rate. The local rate began to increase in 2014, and was significantly higher than the provincial rate in both 2015 and 2016. The rate of HIV/AIDS infections peaked in 2016 at 12.8/100,000, representing the highest number of new cases ever reported I none year in the Middlesex-London region (Figure 9.1.13).

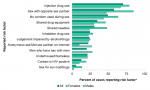

In Middlesex-London, the most common risk factor reported by HIV/AIDS cases between 2014 and 2018 was injection drug use (70.3%), followed by sex with an opposite sex partner (57.8%) and having unprotected intercourse (49.2%). Approximately one-third of cases reported sharing needles (30.8%) or other drug equipment (34.6%). Experiencing homelessness or being underhoused was reported by 21.1%. Anonymous sex and meeting sex partners on the Internet was an emerging risk factor reported by 22.2% of cases (Figure 9.1.14).

There were some important differences in the risk factors reported by female and male HIV/AIDS cases during the same time period. A greater proportion of females than males reported injection drug use as a risk factor (78.8% and 66.9%, respectively). As well, the proportion of female cases reporting sharing needles (48.1%) was double the proportion reported by males (24.1%); there was also a noticeable difference in the proportion of females who shared drug equipment compared to males (46.2% and 30.1%, respectively). More than one-quarter of male cases reported engaging in anonymous sex or meeting partners on the Internet (27.1%), compared to 9.6% of female cases. Engaging in sex for survival or drugs was reported by 13.5% of female cases, while the proportion of males who reported this risk factor was low (2.3%) (Figure 9.1.14).

Interpretation:

The risk factor profile of recent HIV/AIDS cases in Middlesex-London differed from the profile elsewhere in Canada.3 For example, 52.5% of HIV/AIDS cases identified across Canada in 2016 were among men who have sex with men, and 11.3% of cases were among people who inject drugs (PWID).3 In contrast, in the same year in Middlesex-London, 15.5% of cases were among men who have sex with men, and 74.1% of cases reported using injection drugs (data not shown).

Middlesex-London has a relatively large population of PWID in which sharing of needles and equipment has been reported2, which may facilitate blood-borne transmission of HIV/AIDS. Further, substance use may contribute to impaired judgement and lead to higher risk behaviours, such as unprotected intercourse and anonymous sex partners, that contribute to transmission through sexual contact. Both these factors may partially account for the unique profile of HIV/AIDS infections among Middlesex-London residents.

In 2016, an outbreak of HIV/AIDS emerged in the Middlesex-London community, largely among PWID. A multifaceted, multi-year community response including many community partners was mobilized, and focused on HIV/AIDS testing and connecting cases to care, as well as harm reduction initiatives for those at risk. The reduction in local HIV/AIDS rates in 2017 and 2018 is felt to reflect the early successes of these initiatives. However, efforts need to be sustained, as PWID are still overrepresented among HIV/AIDS cases, and there are other at-risk groups in the community.

Syphilis

View more information about syphilis.

Syphilis infections may be detected for the first time at a number of different stages of the disease. Some of these stages are infectious, while at other stages the disease is not considered easily transmitted. From 2005 to 2018 the rate of infectious syphilis significantly increased among Middlesex-London residents, from 1.4/100,000 in 2005 to 10.0/100,000 in 2018. Since 2010, the rate of infectious syphilis cases has been higher than the rate of other types of syphilis; this difference was significant in both 2017 and 2018 (Figure 9.1.15).

Across the 14-year time period, rates of all types of syphilis significantly increased among both female and male residents of Middlesex-London. For females, the rate increased from 0.4/100,000 in 2005 to 6.4/100,000 in 2018, while among males the rate went from 6.1/100,000 to 22.0/100,000. In all but two years the rate among males was significantly higher than the rate among females (Figure 9.1.16).

Syphilis rates were higher among males than females across all age groups; the difference was significant in all age groups except those in their 30s. For males, rates were highest among those 40-49 (23.8/100,000) and 50-59 years old (23.6/100,000). Peak rates for females were observed among those 30-34 years of age (8.0/100,000) (Figure 9.1.17).

Between 2005 and 2018, rates of all types of syphilis significantly increased among Middlesex-London residents and Ontario as a whole. The local rate more than quadrupled, from 3.2/100,000 in 2005 to 14.0/100,000 in 2018. Across the entire time period, the rate among Middlesex-London residents was significantly lower than the rate in Ontario in all years except 2011 (Figure 9.1.18).

Interpretation:

For many years, syphilis rates were very low and it was considered a disease of the past. However, syphilis has re-emerged as a common STBBI. From 2005 to 2018 the number of syphilis cases reported among males was more than three times greater than the number of female cases (data not shown), and many were among men who have sex with men (data not shown). Similar to other STBBIs, further efforts may be needed to reduce the spread of syphilis in the Middlesex-London community.

Other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

View more information about chancroid and hepatitis B.

Between 2005 and 2018, there were no cases of chancroid reported among Middlesex-London residents or elsewhere in Ontario. The rate of hepatitis B infections reported in Middlesex-London was low, at 0.5/100,000 across the 14-year time period (Figure 9.1.19).

Interpretation:

Chancroid and acute hepatitis B infections were rare among Middlesex-London residents between 2005 and 2018.

Increases in the number of STBBIs reported each year and the corresponding rate increases may be due to several reasons. For those engaging in higher risk behaviours, STBBIs may be viewed as treatable conditions, rather than as illnesses that can potentially cause long-term or life-threatening health effects. Safer sex practices that protect against the spread of STBBIs, such as the use of barrier methods during intercourse, may be viewed as less necessary than they were in the past.

Between 2005 and 2018, some risk behaviours became more prevalent, such as anonymous and/or increased numbers of sex partners, facilitated by new technologies such as dating apps and websites. This may have contributed to the increased rates of all STBBIs reported among Middlesex-London residents. New health promotion strategies that resonate with those who use technology in this way may need to be developed in order to address this emerging issue.

Another reason that STBBI rates may have increased among Middlesex-London residents is that there is a large local population of people who inject drugs (PWID). In recent years, multiple overlapping disease outbreaks have emerged in this high risk population. Blood-borne transmission of STBBIs may occur if needles or other equipment is shared. As well, substance use may contribute to impaired judgement that could lead to higher risk behaviours that facilitate STBBI transmission through sexual contact.

For some STBBIs, screening and testing guidelines have been updated over time. As screening increased, detection of STBBIs may also have increased. This may have contributed to some of the increases in STBBIs observed over the 14-year time period in both Middlesex-London and Ontario.

Sexual Health and Sexually Transmitted/Blood-Borne Infections Prevention and Control Protocol, 2018

References:

1. Martin I, Jayaraman G, Wong T, Liu G, Gilmour M. Trends in antimicrobial resistance in Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolated in Canada: 2000-2009. Sex Transm Dis [Internet]. 2011 Oct [cited 2019 May 29];38(10):892-8. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/stdjournal/fulltext/2011/10000/Trends_in_Antimi...

2. Middlesex-London Health Unit. A profile of people who inject drugs in London, Ontario: report on the Public Health Agency of Canada I-Track survey, phase 3, Middlesex-London, 2012 [Internet]. London (ON): Middlesex-London Health Unit; 2013 Nov [cited 2019 May 29]. 22 p. Available from: https://www.healthunit.com/uploads/public-health-agency-of-canada-i-trac...

3. Public Health Agency of Canada. Summary: estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and Canada’s progress on meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets, 2016 [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2018 Jul [cited 2019 May 29]. 18 p. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-co...

Last modified on: July 25, 2019

Jargon Explained

Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections

Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBIs) are those that can be spread from an infected person to others through sexual contact, or through blood, such as when injection equipment is used by more than one person.