Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour

Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour

Chronic disease has been shown to be attributable, in large part, to physical inactivity and sedentary behaviour. The health care costs associated with these diseases are substantial.1 Canada has 24-Hour Movement and Activity Guidelines to help reduce health risks in the population.2 About two thirds of the Middlesex-London adult population self reported physical activity at a level consistent with national recommendations. However, a much lower percent of youth aged 12 to 17 were considered active; only about one in five. Half the population reported some use of active transportation. The percent reporting active transportation in the urban population was higher than in the rural population. It was also higher in the lowest income group compared to higher income groups. Sedentary behaviour occurs in the whole population, including in those who are physically active.

| Meeting Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines | Hours of Sedentary Behaviour |

| Active Transportation |

Meeting Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines

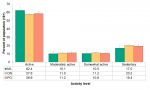

Nearly two thirds (62.4%) of the Middlesex-London population aged 18 and over were active according the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines (Guidelines) in 2015/16.1 About one in 10 people was moderately active (10.1%) and somewhat active (10.5%), however, nearly 20%, or one in five, were sedentary. These proportions were not significantly different than the provincial rates or those of the Peer Group (Figure 6.2.1).

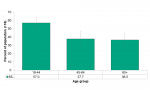

The youngest age group (18–44) had the highest percent of people who were active according to the Guidelines. The rate in this group was significantly higher than those aged 65 and older. Similarly, those in the 65+ population had nearly four times the rate of sedentary status (32.7%) compared to 18 to 44 year olds (7.9%) (Figure 6.2.2).

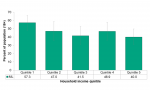

Generally, as income level increased, the proportion of people who were active also increased. The one exception was that the lowest income quintile was more active than the second lowest quintile. The percent of people who were active in the highest income group (Q5) (71.3%) was significantly higher than the percent of people who were active in the second lowest quintile (Q2) (46.9%). A general decrease in the percent of people who were reported as having sedentary behaviour was seen as income increased (Figure 6.2.3).

Less than one in five youth aged 12–17 in Middlesex-London were active in 2015/16 (17.7%) according to the Guidelines. While lower than the provincial and Peer

Group rates, the difference was not significant.

Interpretation

For children and youth, being active can help improve movement skills, develop confidence and increase feelings of happiness. In adults, adequate physical activity can help reduce the risk of chronic disease, increase fitness and improve overall mental health and wellbeing. Research has shown the benefits of getting sufficient physical activity and limiting sedentary behaviour; one study demonstrated that children who met guideline recommendations had higher scores for physical literacy domains such as physical competence, and motivation and confidence.3 As was seen in Middlesex-London, the percent of adults meeting guidelines for physical activity in a national survey in the U.S. increased as household income increased.4

Active Transportation

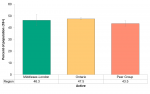

Nearly half the population (46.3%) of Middlesex-London aged 18 and above reported using active transportation during the past week when asked on a survey in 2015/16. This was not significantly different than the rate in Ontario or the Peer Group (Figure 6.2.4).

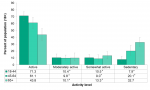

Those in the youngest adult age group (18–44) had a higher percent of people who reported using active transportation in the past week (57.0%) compared to the 45–64 age group (37.7%) and the 65+ age group (36.5%). The difference was statistically significant (Figure 6.2.5).

About 85% of the youth population aged 12–17 reported using active transportation in the past week. This was not statistically different than Ontario and the Peer Group.

Generally, there was a decrease in the use of active transportation as income quintile increased in Middlesex-London. Although not statistically significant, Q1 (the lowest income group) had a higher rate of use of active transportation (57.3%) compared to the highest income group (40.0%) (Figure 6.2.6).

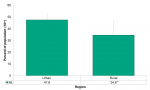

Those who lived in urban areas (47.6%) had a higher rate of use of active transportation compared to those in rural areas (34.6%). The difference is not significant (Figure 6.2.7).

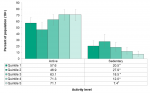

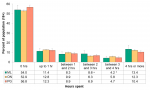

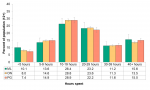

For adults, 54.0% of the population used no active transportation in the past week when asked on survey in 2015/16. About 11% used an active transportation method for a duration of one hour, 8.3% for two hours and 8.6% for three hours each in the past week. These rates were not significantly different than the provincial or peer group rates (Figure 6.2.8).

For youth between the ages of 12–17 about one in five (19.4%) used no active transportation. About half (48.7%) used a form of active transportation for up to four hours and 31.9% used active transportation four or more hours in the past week when asked on survey in 2015/16. There were no significant differences between Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group.

Interpretation

Active transportation is defined as any form of human powered travel such as walking, biking, rollerblading or skateboarding and has many benefits for the individual and the community as a whole. It increases physical activity and is a healthier form of transportation then vehicular travel. It is better for the environment as it reduces carbon emissions. Well-designed active transportation infrastructure can have positive impacts on the local economy and have lower costs for individuals.5 A Canadian study showed that active transportation to school in children and youth was significantly more likely in larger communities rather than smaller communities. It was also higher in lower income groups compared with higher income groups.6 These findings are similar to those of Middlesex-London showing higher rates of active transportation in urban populations and in lower income quintiles.

Hours of Sedentary Behaviour

When looking at hours of sedentary behaviour, the greatest proportion of the total population (aged 12 and older) reported 10–19 hours of sedentary behaviour in the week prior to being surveyed in 2015/16 (26.4%) in Middlesex-London. The next most common was 20–29 hours at 23.2%. More than one in six (15.6%) were sedentary for 40 or more hours per week. There were no significant differences between Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group (Figure 6.2.9).

Interpretation

Sedentary behaviour should be minimized, especially when it involves screen time. A large percent of the population reported sedentary behaviour for more than 40 hours a week. Sedentary behaviour occurs in the whole population, including in those who are physically active. This count did not include the time spent sitting to read or at work or school, so total sedentary behaviour likely greatly exceeds the amount described here.

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

References:

1. Janssen I. Health care costs of physical inactivity in Canadian adults. Applied Physiology, Nutrition & Metabolism [Internet]. 2012 Aug [cited 2019 May 7];37(4):803–6. Available from: https://www.nrcresearchpress.com/doi/pdf/10.1139/h2012-061

2. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; c2019 [cited 2019 Apr 17]. Available from: https://csepguidelines.ca/

3. Belanger K, Barnes JD, Longmuir PE, Anderson KD, Bruner B, Copeland JL, Gregg MJ, Hall N, Kolen AM, Lane KN, Law B, MacDonald DJ, Martin LJ, Saunders TJ, Sheehan D, Stone M, Woodruff SJ, Tremblay MS. The relationship between physical literacy scores and adherence to Canadian physical activity and sedentary behaviour guidelines. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2018 Oct 2 [cited 2019 Apr 17];18(2 Suppl):1042. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-018-58...

4. Hawkins L, Montgomery M. Quickstats: percentage* of adults who met federal guidelines for aerobic physical activity,(†) by poverty status(§) - National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2014(¶). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2016 May 6 [cited 2019 Apr 17];65(17):459. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/wr/pdfs/mm6517a6.pdf

5. Transport Canada. Active transportation in Canada: a resource and planning guide [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Transport Canada; 2011 [cited 2019 Apr 17]. 100 p. Available from: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2011/tc/T22-201-2011-en...

6. Gray CE, Larouche R, Barnes JD, Colley RC, Bonne JC, Arthur M, Cameron C, Chaput J-P, Faulkner G, Janssen I, Kolen AM, Manske SR, Salmon A, Spence JC, Timmons BW, Tremblay Ms. Are we driving our kids to unhealthy habits? Results of the active healthy kids Canada 2013 report card on physical activity for children and youth. Int J Environ Res Public Health [Internet]. 2014 Jun 5 [cited 2019 Apr 17];11(6):6009–20. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4078562/

Last modified on: July 9, 2019

Jargon Explained

Active for Adults (18-64) and Older Adults (65+)

at least 150 minutes of moderate- to vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, in bouts of 10 minutes or more according to the Canadian Physical Activity Guidelines.2

Active for Youth (12-17)

At least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity physical activity daily according to the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth. Although vigorous intensity activity is recommended at least 3 days per week it was not considered in this analysis.2

Sedentary behaviour

Time spent in the last seven days doing sedentary activities such as using a computer (including playing computer games), using the Internet, playing video games and watching television or videos. For all activities, the time spent at school or work is excluded. Time spent reading is not included.

Active transportation

Includes all time spent traveling in active ways in the 7 days prior to the survey interview. Active transportation is any form of human powered travel such as walking, biking, rollerblading, skateboarding, etc.