Cancer

Cancer

Cancer is not just one disease, but a collection of related diseases that can happen almost anywhere in the body. Cancer happens when cells in the body begin to divide without stopping. The cancer cells can spread into nearby tissues or other parts of the body, and can form growths called tumours.1 There are more than 100 types of cancer and they are usually named after the organ or tissue where the cancer starts.2 Cancer is a chronic disease of public health importance in which Ontario public health units have a mandate to reduce its burden through interventions that promote health and help to prevent disease.3 Incidence rates of cancer decreased slightly over time for Middlesex-London from 2011 to 2014. Breast cancer had the highest incidence rates for females, while prostate cancer had the highest incidence rates for males. Lung cancer was the third leading cause of death in Middlesex-London from 2013 to 2015. For some cancers, screening increases the chances of detection before it has the chance to grow and spread.

| All cancers | Malignant melanoma |

| Colorectal cancer | Oral cancer |

| Lung cancer | Lymph and blood cancer |

| Cervical cancer | Prostate cancer |

| Female breast cancer |

All cancers

Among the Middlesex-London population age 12 years and older, 1.4% reported having cancer in 2015/16 (Figure 7.2.1). The percentage was similar compared to Ontario (1.3%).

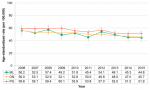

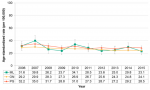

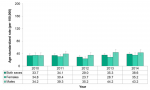

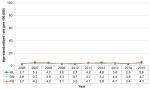

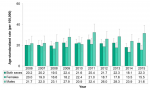

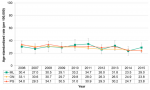

Incidence rates of all cancers in Middlesex-London were slightly higher compared to Ontario from 2011 to 2014, but the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 7.2.2). Rates decreased slightly over time in both Middlesex-London and Ontario from 2011 to 2014.

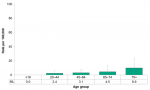

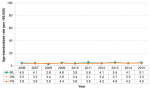

Incidence rates of cancer were significantly higher in males compared to females in Middlesex-London from 2010 to 2014 (Figure 7.2.3).

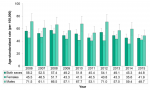

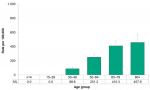

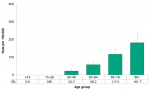

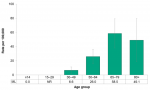

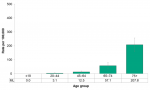

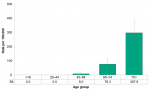

When comparing across all age groups, the incidence rate of cancer in Middlesex-London in 2014 increased significantly with age and was highest among the oldest age group (age 80+) (Figure 7.2.4).

The Preventable Mortality section contains data showing that cancer was the leading cause of preventable mortality among Middlesex-London residents age 45 to 74 from 2013 to 2015.

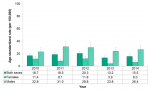

Death rates from all cancers were significantly higher among the rural population of Middlesex-London compared to the urban population from 2013 to 2015 (Figure 7.2.5).

Interpretation

It is estimated that about 1 in 2 Canadians will develop cancer in their lifetime, and about 1 in 4 will die of cancer.4 Cancer is the leading cause of death in Canada and accounted for 30% of all deaths in 2012.5 Since 1988, the rate of cancer deaths in Canada has decreased by more than 35% in males and 20% in females due to progress made in terms of early detection, diagnosis, and treatment.4

The number of new cancer cases diagnosed each year has risen steadily between 1984 and 2019 because of the growing and aging Canadian population. However, rates of cancer have actually decreased in Canada since 2011 when the data have been adjusted for age.

Age is the most important risk factor for cancer. In Canada, cancer rates peak in males age 85 years and older, and in females age 80 to 84 years.4

Colorectal cancer

Incidence rates of colorectal cancer in Middlesex-London decreased slightly over time from 2010 to 2014 and were not significantly different compared to Ontario (Figure 7.2.6).

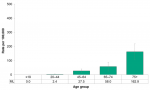

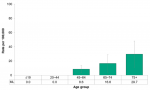

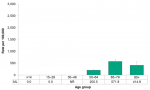

When comparing across all age groups, the incidence rate of colorectal cancer in Middlesex-London in 2014 increased with age and was highest among those age 80 and older (471.4 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.7).

Incidence rates of colorectal cancer were higher among males compared to females in Middlesex-London from 2010 to 2014, however the differences were not always statistically significant (Figure 7.2.8).

The Leading Causes of Death section contains data showing that colorectal cancer was the sixth leading cause of death in Middlesex-London from 2013 to 2015.

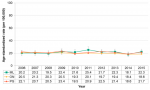

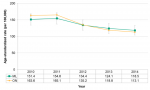

Rates of death due to colorectal cancer in Middlesex-London were not significantly different compared to Ontario from 2006 to 2015 (Figure 7.2.9). Rates in Middlesex-London decreased over time from 2007 to 2015.

Interpretation

Colorectal cancer develops in the colon or the rectum of the large bowel, a part of the digestive system. It is estimated that 1 in 13 men, and 1 in 16 women will develop colorectal cancer in their lifetime.6 Risk factors for colorectal cancer include (but are not limited to): age (e.g., 50 years and older), sex (e.g., males), family history of colorectal cancer, heavy alcohol use, smoking, ethnicity (e.g., Ashkenazi Jews), diet (e.g., red meat, processed meats, low-fibre), and being overweight or obese.6, 7

When detected and treated early, 9 out of 10 people with colorectal cancer can be cured.7 The type of screening depends on a person’s risk of getting colorectal cancer. A person is considered at “average risk” for colorectal cancer if the person: is aged 50 to 74, does not have first-degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) who has been diagnosed with colorectal cancer, and has no signs or symptoms of colorectal cancer. The fecal immunochemical test (FIT) is the recommended screening test for those at “average risk”, while a colonoscopy is recommended for those at higher risk.8

Lung cancer

Incidence rates of lung cancer in Middlesex-London were not significantly different compared to Ontario from 2010 to 2014 (Figure 7.2.10). During this period, rates remained stable over time.

Incidence rates of lung cancer were higher among males compared to females in Middlesex-London from 2010 to 2014, however differences were generally not statistically significant (Figure 7.2.11).

When comparing across all age groups, the incidence rate of lung cancer increased with age and was highest among the age 80 and older (432.1 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.12).

The Leading Causes of Death section contains data showing that lung cancer was the third leading cause of death in Middlesex-London from 2013 to 2015.

Death rates due to lung cancer decreased over time in Middlesex-London from 2006 to 2015 and were not significantly different compared to Ontario (Figure 7.2.13).

Death rates due to lung cancer were higher among males in Middlesex-London compared to females from 2006 to 2015, however the differences were often not statistically significant (Figure 7.2.14).

Interpretation

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in Canada, responsible for approximately 26% of cancer deaths.9 Lung cancer may not cause any signs or symptoms in its early stages10; so by the time it does cause symptoms, the cancer has usually spread to other parts of the body or has grown too big for treatment to work.11

Smoking tobacco is the main cause of lung cancer. Other risk factors for developing lung cancer include: exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke, family history of lung cancer, and exposure to air pollution (e.g., vehicle exhaust), radon gas, asbestos, and petroleum products.9, 11

Cervical cancer

Incidence rates of cervical cancer in Middlesex-London were generally lower compared to Ontario from 2010 to 2014, but the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 7.2.15).

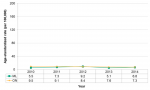

Death rates due to cervical cancer in Middlesex-London were not significantly different compared to Ontario from 2006 to 2015 (Figure 7.2.16).

When compared across all age groups, the death rate due to cervical cancer increased with age and was highest among those age 75 and older (9.9 per 100,000), however the differences between age groups were not statistically significant (Figure 7.2.17).

Interpretation

Cervical cancer develops in the cells of the cervix, a narrow passageway that connects the uterus to the vagina.12 Cervical cancer is the 15th most common cancer among women in Ontario, and is more common in younger women compared to other cancers (highest rate is among women age 40 to 44).13 The main risk factor for developing cervical cancer is the human papilloma virus (HPV), a sexually transmitted virus.12

Cervical cancer is almost completely preventable with the HPV vaccine, regular Pap tests, and appropriate and timely follow-up of abnormal Pap test results.14 A Pap test is a procedure where a small sample of cells are taken from the cervix, and then examined under a microscope to determine whether abnormal cells may be present.15

In Ontario, a Pap test is recommended every three years for:

• women age 21 years and older who are or have been sexually active, and

• transgendered men who have a cervix, who are age 21 years and older, and who are or have been sexually active.14

Female breast cancer

Incidence rates of female breast cancer were lower in Middlesex-London compared to Ontario in 2013 and 2014, but the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 7.2.18).

When comparing across all age groups, the incidence rate of female breast cancer in Middlesex-London in 2014 increased with age and was highest among those age 80 and older (457.6 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.19).

For the female population of Middlesex-London, breast cancer was the sixth leading cause of death from 2013 to 2015 (Figure 3.4.2).

Death rates due to female breast cancer in Middlesex-London were not significantly different compared to Ontario from 2006 to 2015 (Figure 7.2.20).

When comparing across all age groups, the rate of death due to female breast cancer in Middlesex-London in 2015 increased with age and was highest among those age 75 and older (162.9 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.21).

Interpretation

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women in Canada. It is estimated that 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer in her lifetime.16

Risk factors for breast cancer include, but are not limited to: age (e.g., 50 years and older), family history of breast cancer, inherited genetic mutations (e.g., BRC1 and BRCA2), reproductive status (e.g., early menstrual periods, late menopause), hormone use (e.g., hormone replacement therapy, oral contraceptive pills), alcohol use, and being overweight or obese.16, 17

Breast x-rays called mammograms are used to screen and detect breast cancer. In Ontario, a mammogram is recommended every two years for women age 50 years and older and who are at average risk for breast cancer. Women age 30 to 69 years may also be referred for screening if they are considered at high risk.18

Malignant melanoma

Incidence rates of malignant melanoma were generally significantly higher in Middlesex-London compared to Ontario from 2010 to 2014 (Figure 7.2.22).

The incidence rate of malignant melanoma in Middlesex-London in 2014 increased with age and was highest among the oldest age group (age 80+) (Figure 7.2.23).

Incidence rates of malignant melanoma were higher among males compared to females in Middlesex-London in 2014, but the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 7.2.24).

Rates of death due to malignant melanoma were not significantly different in Middlesex-London compared to Ontario from 2006 to 2015 (Figure 7.2.25). Rates remained relatively stable over this time period.

Interpretation

Malignant melanoma is a type of cancer that develops in melanocytes, specialized cells that produce pigment called melanin.1 Most melanomas form on the skin, but they can also form in other pigmented tissues, such as the eye.1 The main risk factor for developing malignant melanoma is exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation through sunlight, tanning beds, and sun lamps.4

Treatment for malignant melanoma is effective when detected and treated in its early stages; however, it is difficult to stop once it has spread to other parts of the body.19

Oral cancer

Incidence rates of oral cancer were not significantly different in Middlesex-London compared to Ontario from 2010 to 2014 (Figure 7.2.26).

Incidence rates of oral cancer were significantly higher in males compared to females in Middlesex-London from 2010 to 2014 (Figure 7.2.27).

The incidence rate of oral cancer was highest among the 65–79 age group (58.5 per 100,000), followed by those age 80 and older (49.1 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.28).

Rates of death due to oral cancer were not significantly different in Middlesex-London compared to Ontario from 2006 to 2015 (Figure 7.2.29).

When comparing across all age groups, the rate of death due to oral cancer in Middlesex-London in 2015 increased with age and was highest among those age 75 and older (29.7 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.30).

Interpretation

Oral cancer can develop in different areas of the month, including: lips, gums, tongue, tonsils, salivary glands, and back of the throat.20 The lymph nodes in the neck are the most common place oral cancer spreads.21

Risk factors for oral cancer include (but are not limited to): age (e.g., 45 years and older), smoking or using tobacco products, alcohol use, gender (e.g., male), diet (e.g., low in fruits and vegetables), human papilloma virus (HPV) infection, sun exposure, and poor oral health. While tobacco and alcohol use increases the risk of developing oral cancer, about one in four cases occur in people who do not use either product.20

While oral cancer can develop at any age, the incidence is highest among people over the age of 60.20

Lymph and blood cancer

The Leading Causes of Death section contains data showing that lymph and blood cancers were the seventh leading cause of death in Middlesex-London from 2013 to 2015.

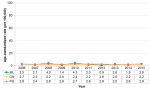

Death rates due to lymph and blood cancer in Middlesex-London were not significantly different compared to Ontario from 2006 to 2015 (Figure 7.2.31).

Death rates from lymph and blood cancer were generally higher among males compared to females in Middlesex-London from 2006 to 2015, although the difference was only statistically significant in 2015 (Figure 7.2.32).

When comparing across all age groups, the death rate due to lymph and blood cancer in Middlesex-London in 2015 increased with age and was highest among those age 75 and older (207.8 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.33).

Interpretation

Blood cancer is an umbrella term for cancers that develop in blood cells, the bone marrow, lymph nodes, and other parts of the lymphatic system.22 Blood cancers represent approximately 10% of all cancer diagnoses in Canada.23 There are three main types of blood cancers: leukemia, lymphoma (such as Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma), and multiple myeloma.24

Leukemia is a blood cancer that develops in the blood stem cells. There are many different types of leukemia; they are grouped based on the type of blood cells they developed from (lymphoid or myeloid stem cells) and how quickly it grows (acute vs. chronic).25

Lymphoma is a blood cancer that develops in the lymphocytes, which are types of white blood cells that help fight infection.26 The abnormal lymphocytes can form tumours called lymphomas, which can form in the lymph nodes, liver, spleen, or other parts of the body.22 Lymphomas are divided into two categories: non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma. The abnormal cells of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma look and behave differently from Hodgkin lymphoma, and so the two are treated differently.27

Multiple myeloma is a blood cancer that develops in the bone marrow.22

It is estimated that 21,000 Canadians will be diagnosed with a blood cancer in 2019. This includes 6,700 cases of leukemia, 10,000 cases of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, 1,000 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma, and 3,300 cases of multiple myeloma.23

Prostate cancer

Incidence rates of prostate cancer decreased over time in Middlesex-London and Ontario from 2010 to 2014 (Figure 7.2.34). Incidence rates in Middlesex-London were slightly higher compared to Ontario in 2013 and 2014, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The incidence rate of prostate cancer was highest among those age 65 to 79 (571.8 per 100,000) in Middlesex-London in 2014, followed by those age 80 and older (414.8 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.35).

For the male population of Middlesex-London, prostate cancer was the eighth leading cause of death from 2013 to 2015 (Figure 3.4.2).

Death rates due to prostate cancer were not significantly different in Middlesex-London compared to Ontario from 2006 to 2015 (Figure 7.2.36).

When comparing across all age groups, the death rate due to prostate cancer increased significantly with age and was highest among those age 75 and older (297.8 per 100,000) (Figure 7.2.37).

Interpretation

Prostate cancer develops in the cells of the prostate, a gland that produces semen and is located below the bladder, in front of the rectum.28 Prostate cancer is the most common type of cancer in men.29 It is estimated that 1 in 7 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer in his lifetime.30

The cause of prostate cancer is unknown; however, rates of prostate cancer have been highest in men who: are age 50 years and older, have a family history of prostate cancer, and are of African ancestry.29

Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

Chronic Disease Prevention Guideline, 2018

References:

1. National Cancer Institute. What Is Cancer? [Internet]. Rockville, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2015 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer

2. Canadian Cancer Society. What Is Cancer? [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2017 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-101/what-is-cancer/?r...

3. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/d...

4. Canadian Cancer Statistics Advisory Committee. Canadian Cancer Statistics 2019 Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society, 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: http://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20...

5. Public Health Agency of Canada. Health Status of Canadians 2016: A Report of the Chief Public Health Officer [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada, 2016 [cited 2019 Sep 23]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-publ...

6. Public Health Agency of Canada. Colorectal Cancer [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2017 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/cancer/...

7. Cancer Care Ontario. Screening for Colorectal Cancer [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for ONtario; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/types-of-cancer/colorectal/screening

8. Government of Ontario. Colon Cancer Testing and Prevention [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2014 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/colon-cancer-testing-and-prevention

9. Public Health Agency of Canada. Lung Cancer [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/cancer/...

10. Canadian Cancer Society. Symptoms of Lung Cancer [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/lung/signs-and-s...

11. Cancer Care Ontario. Lung Cancer [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/types-of-cancer/lung

12. Public Health Agency of Canada. Cervical Cancer [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2017 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/chronic-diseases/cancer/...

13. Cancer Care Ontario. Cervical Cancer [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/types-of-cancer/cervical

14. Government of Ontario. Cervical Cancer Testing and Prevention [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2014 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/cervical-cancer-testing-and-prevention

15. Canadian Cancer Society. Pap Test [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Socity; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/diagnosis-and-treatment/test...

16. Public Health Agency of Canada. Breast Cancer in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2017 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-co...

17. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer? [Internet]. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health & HUman Services; 2018 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/basic_info/risk_factors.htm

18. Government of Ontario. Ontario Breast Screening Program [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2014 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/ontario-breast-screening-program

19. Public Health Agency of Canada. Skin Cancer [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2018 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/sun-safety/skin-cancer.html

20. Public Health Agency of Canada. Oral Cancer Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2018 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/oral-diseases-conditions...

21. Canadian Cancer Society. What Is Oral Cancer? [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Socity; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/oral/oral-cancer...

22. Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of Canada. About Blood Cancers [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Leukemia & Lymphoma Society of Canada; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.llscanada.org/disease-information/facts-and-statistics

23. Media Backgrounder: Blood Cancer in Canada [press release]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society, 2019 Sep 4 2019.

24. Canadian Cancer Society. What You Need to Know About Blood Cancer in Canada [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: http://www.cancer.ca/en/about-us/our-stories/what-you-need-to-know-about...

25. Canadian Cancer Society. What Is Leukemia? [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/leukemia/leukemia...

26. Canadian Cancer Society. What Is Hodgkin Lymphoma? [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/hodgkin-lymphoma/...

27. Canadian Cancer Society. What Is Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma? [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Canadian Cancer Society; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/non-hodgkin-lymph...

28. Cancer Care Ontario. Prostate Cancer [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2019 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/types-of-cancer/prostate

29. Government of Ontario. Prostate Cancer Screening Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2014 [cited 2019 Sep 25]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/prostate-cancer-screening

30. Public Health Agency of Canada. Prostate Cancer in Canada [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2017 [cited 2019 Sep 24]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/prostate-cancer.html

Last modified on: November 18, 2019

Jargon Explained

Self-reported cancer

The percent of individuals age 12 and older who reported having cancer.

Incidence rate of cancer

The number of new cancer cases diagnosed per year.