Road and Off-road Safety

Road and Off-road Safety

Rates of motor vehicle collision injuries seen in emergency departments are on the rise with an increase seen between 2014 and 2017, after years of decline. With data not quite as recent, trends for alcohol-related collisions causing injury or death have declined, mirrored by lowering self-reported rates of drinking before driving. Always wearing a seat belt, was reported by almost 90% of the population, however continued work is needed to increase the use of bicycle helmets and decrease rates of driving and texting.

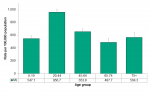

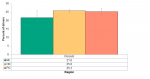

The rate of deaths from motor vehicle collisions (MVC) in Middlesex-London did not change significantly between 2005 and 2012. There was also no observed difference in death rates due to MVC between Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group health units (Figure 4.4.1).

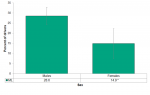

The rate of death due to MVCs in males (9.2 per 100,000) was significantly higher than in females (2.4 per 100,000) during the 2010-2012 time period (Figure 4.4.2).

While there were large differences in urban (4.8 per 100,000) and rural (14.8) rates of death due to MVCs, the difference was not statistically significant. Small counts of deaths between 2010 and 2012 are contributing to the large confidence interval in the rural population (Figure 4.4.3).

The rate of MVCs-related emergency department visits declined significantly between 2005 and 2014, but then began to rise again. The current trend is upward and the rate seen in 2017 (717.4 per 100,000) was similar to that seen in 2010, erasing any gains of reduced MVC injuries seen in the years between. An increasing trend was also seen in the provincial and Peer Group rates (Figure 4.4.4).

Rates of deaths due to MVCs also showed a decline over the time period of 2005 to 2010 but then began to rise in 2011 and 2012 for ML or the other comparators, although not significantly (Figure 4.4.4).

The 20-44 age group had the highest rate of MVC-related ED visits in 2017, significantly higher than all other age groups (956.7 per 100,000) (Figure 4.4.5).

Those in the rural population experienced a 50% higher rate of MVCs than their urban counterparts (1,089.8 vs. 700.0 per 100,000). This difference is statistically significant. Rates did not differ by sex (not shown).

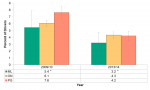

The rate of MVCs involving a personal injury or death declined significantly over time between 2008 (729.2 per 100,000) to 2015 (636.1) in Middlesex-London. A similar downward trend was seen in Ontario over the same time period (Figure 4.4.6). Compared to data from 1988, the 2015 rates were a third of what they once were (not shown).

The rate of collisions causing injuries was consistently higher in Middlesex-London than in Ontario (Figure 4.4.6).

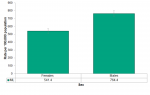

Males (764.4 per 100,000) were significantly more likely to be the driver in a MVC causing personal injury or death than females (541.4) for the time period averaged between 2013 and 2015 (Figure 4.4.7).

There was a significant and substantial decrease in the rate of MVCs causing injury or death that involved alcohol between 2008 (25.8 per 100,000) and 2015 (13.4) (Figure 4.4.8). The 2015 rate is seven times lower than it was in 1988 (not shown).

Middlesex-London rates of alcohol involvement in MVCs causing injury or death were consistently higher than those of the province (Figure 4.4.8).

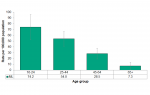

There was a downward trend in the rate of MVCs causing personal injury or death involving alcohol as age group increased. Those in the 16-24 age group had the highest rate (74.2 per 100,000) compared to 7.3 in those age 65 and over (Figure 4.4.9).

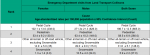

Collisions involving bicycles are the most common type of transport collision in Middlesex London, after MVCs. A bicycle collision may have included a motor vehicle but injury rates presented represent the injuries of those on the bicycle. The rate of emergency department visits for injuries for bicycle collisions was, on average 186.6 per 100,000 people per year in the years 2015 to 2017. Males had more than double the rate of injuries from cycling then females (Figure 4.4.10).

Pedestrians are the next most common to be injured with 58.4 per 100,000 on average per year, with no significant differences between sexes (Figure 4.4.10).

All-terrain vehicles, excluding snowmobiles, had a rate of 31.7 per 100,000 ED visits and snowmobiles had a rate of 6.0 per 100,000. In both of these types of vehicles, males were significantly more likely to go to the emergency department with an injury than females. In the case of ATVs, the rate was three times higher in males than in females and for snowmobiles it was seven times higher (Figure 4.4.10).

Seat belt use

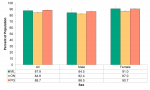

In 2013/14 almost 90% of the population aged 12 and older reported that they always wear their seat belt as passengers in a vehicle (Figure 4.4.11).

This was slightly higher than in 2009/10, but the increase was not statistically significant. Similar increases from 2009/10 to 2013/14 were also seen in Ontario and the Peer Group and these were statistically significant (not shown).

Females were more likely to wear a seatbelt than males. The difference was statistically significant in both Ontario and the Peer Group, but not in Middlesex-London (Figure 4.4.11).

Females in Middlesex-London were significantly more likely to wear a seatbelt than females in Ontario (Figure 4.4.11).

In Middlesex-London those aged 65+ were more likely to wear a seatbelt compared to younger people in Middlesex-London and compared to those 65+ in Ontario and the Peer Group (not shown).

Driving after alcohol use

In 2013/14 the proportion of people who reported that they drove after consuming two or more drinks in the hour before they drove was 3.2% in Middlesex-London. This was lower than in 2009/10. Although the decrease was not statistically significant in Middlesex-London, a significant decrease was seen in both Ontario and the Peer Group proportions (Figure 4.4.12).

Males were considerably more likely to drink and drive compared to females and a similar difference was seen in Middlesex-London, the Peer Group and Ontario. The estimates for Middlesex-London were too small to report, but in Ontario 7.2% of males reported drinking and driving compared to 1.1% among females (not shown).

Cell phone use while driving

About 20% of the population in Middlesex-London reported ever using a cell phone while driving in 2013/14. This compares to about 25% of the Ontario population and the Peer Group, however the difference between geographic comparators isn’t statistically significant (Figure 4.4.13).

Males were significantly more likely than females to report ever using a cell phone while driving. Note that this excludes hands free use (Figure 4.4.14).

There were no other significant differences observed in behaviours related to cell phone use while driving between urban/rural populations, age groups, income, education or employment groups (not shown).

A much smaller proportion reported often using hands free when using their cell phone in the car. It was 13.8% in Middlesex London, which was significantly less than the Ontario rate (Figure 4.4.15).

Like cell phone use in general, hands free use is more common among males than females. While the trend is not statistically significant, the rate of hands free use increases as income increases (not shown).

Helmet use while bicycling

Approximately one in 10 reported always wearing a helmet when riding a bicycle in Middlesex-London between 2011 and 2014 in the population age 12 and older. There were no significant differences between Middlesex-London and its geographic comparators, Ontario and the Peer Group (Figure 4.4.16).

Those who were very young (age 12-17) were significantly more likely to always wear a helmet while riding a bicycle (22.0%) compared to those in the age 65 and older age group (4.7%) (Figure 4.4.17).

About 12% of those in the age groups in between 18 and 64 reported always wearing a helmet (Figure 4.4.17).

The population who reported always wearing a helmet when riding a bicycle differs by household income. The trend shows increased proportions of people always using a helmet as household income increases. This was 6.1% of those in the lowest income bracket compared to 20.7% in the highest income group in Middlesex-London (Figure 4.4.18).

Interpretation

MVCs had the highest total injury related costs (including both direct and indirect costs) of all transport incidents in 2010 at $620 million in Ontario. Injuries due to pedal cycle or bicycling were the next highest with $161 million followed by pedestrian injuries at $141 million. ATVs with snowmobiles were $122 million in total costs.1

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

References:

1. Parachute. The cost of injury in Canada [Internet]. Version 2.2. Toronto (ON): Parachute; 2015 [2019 Feb 10]. 177 p. Available from: http://www.parachutecanada.org/downloads/research/Cost_of_Injury-2015.pdf

2. Ministry of Transportation [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Government of Ontario, Ministry of Transportation; c2012-2019. Impaired driving; c2009 [modified 2019 Jan 2; cited 2019 Feb 10]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: http://www.mto.gov.on.ca/english/safety/impaired-driving.shtml

3. Ialomiteanu AR, Hamilton HA, Adlaf EM, Mann RE. CAMH monitor e-report 2017: substance use, mental health and well-being among Ontario adults, 1977–2017 [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Centre for Addiction and Mental Health; 2018 [cited 2019 Feb 11]. 290 p. (CAMH research document series; no. 48). Available from: https://www.camh.ca/-/media/files/pdfs---camh-monitor/camh-monitor-2017-...

4. Ministry of Transportation [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Government of Ontario, Ministry of Transportation; 2015 Oct. Distracted driving; 2016 Jun 15 [updated 2019 Jan 22; cited 2019 Feb 10]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/distracted-driving

5. Ministry of Transportation [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Government of Ontario, Ministry of Transportation; c2012-2019. Bicycle safety; c2009 [modified 2018 Apr 18; cited 2019 Feb 10]; [about 5 screens]. Available from: http://www.mto.gov.on.ca/english/safety/bicycle-safety.shtml

Last modified on: March 15, 2019

Jargon Explained

Income quintile

This is a measure that divides the entire population into five equal groups, also known as quintiles. Approximately 20% of the population is in each group. The lowest income quintile is the group with the lowest total household income, after taxes.

Land Transport Collision

Land transport collisions include injuries sustained during a motor vehicle collision, whether as a driver or passenger in the vehicle, as a pedestrian, a cyclist, a motorcyclist. They also include injuries sustained on all-terrain vehicles, snowmobiles and other types of vehicles travelling on land.

Small counts

The stability of a rate is dependent on the number of events that contribute to that rate. Therefore, rates in small populations are often unstable due to the relatively small number of events that occur each year. When comparing trends over time between Middlesex-London, the province and the Peer Group, we often see a larger fluctuation in rates locally than for Ontario, in which the trends are fairly smooth from year to year – this concept needs to be considered when interpreting the time trends and the confidence intervals in this resource.