Self-rated health and mortality

Self-rated health and mortality

A goal of public health units in Ontario is to achieve optimal child and youth health.1 Most youth in Middlesex-London perceived themselves to be in very good health, and reported having positive mental health and a sense of community belonging. Compared to all other age groups in Middlesex-London, children and youth had the lowest mortality rate. For children under the age of ten, the two leading causes of death were birth defects and brain cancer. For older children and youth, motor vehicle collisions and suicide were the two leading causes of death. Overall, injury and infection were the leading causes of preventable death for children and youth, indicating where continued public health efforts are needed to help reduce deaths from preventable diseases and injuries.

The General Health topic contains data for the overall Middlesex-London population on life expectancy, death from all causes, leading causes of death, preventable mortality, and potential years of life lost.

| Self-rated health | Leading causes of death |

| Death from all causes | Preventable mortality |

Self-rated-health

The Self-rated Health section contains data for the Middlesex-London population age 12 and older on perceived health, perceived mental health, and community belonging.

For Middlesex-London youth age 12–19, 81.1% reported their health as “very good” or “excellent” in 2015/16 (Figure 3.1.3). Across all age groups (age 12 and older), those age 12–19 reported the highest self-rated health.

Most Middlesex-London residents age 12 and older (70.2%) reported having positive mental health (“very good” or “excellent”) in 2015/16 (Figure 3.1.7). This is comparable to Ontario where 71.1% reported having positive mental health in 2015/16 (not shown).

Among those age 12–19, 80.7% reported their mental health as “very good” or “excellent” in 2015/2016; the highest percent across all age groups (not shown). This is higher compared to Ontario where 73.4% of those age 12–19 years reported their mental health as “very good” or “excellent” (not shown).

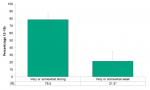

Most youth age 12–19 (78.5%) in Middlesex-London reported having a “very strong” or “somewhat strong” sense of community belonging in 2015/16 (Figure 13.1.1). This is higher in comparison to the general population age 12 and older where 71.5% reported having a “very strong” or “somewhat strong” sense of community belonging (Figure 3.1.8). On the other hand, Figure 13.1.1 also shows that over one in five (21.5%) youth age 12–19 in Middlesex-London reported having a “very weak” or “somewhat weak” sense of community belonging in 2015/16; although the estimate should be interpreted with caution due to high variability.

Interpretation

“Self-perceived health” reflects people’s overall perception of their own health; it includes their overall physical, mental, and social well-being.2 While it is a subjective measure of health, it has been found to be a good predictor of morbidity and mortality3, 4 and healthcare use 5,6. Young Canadians who have social supports in homes, neighbourhoods, schools and peer groups have been found to have better perceived health.7

Death from all causes

The Death From All Causes section contains data on the rate of all-cause mortality in Middlesex-London from 2006–2015. When comparing across all age groups, the 0–19 age group had the lowest mortality rate per 100,000 population (Figure 3.3.2). The mortality rate among males in this age group was almost double that of females (51.4 vs. 26.1 per 100,000, respectively).

Interpretation

Over the lifespan, the probability of dying follows a checkmark shape in Canada; where the probability is higher in the first year of life, then decreases to the lowest levels between the ages of 1 and 14, and then increases through adulthood to reach the highest levels in the senior years.8

Leading causes of death

The Leading Causes of Death section contains data on the leading causes of death in Middlesex-London from 2013 to 2015.

For the 1–9 age group in Middlesex-London, the two leading causes of death were birth defects and brain cancer; these were also the leading causes of death for this age group in Ontario and the Peer Group (Figure 3.4.3). For the 10–19 age group, motor vehicle collisions and suicide were the two leading causes of death in Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group (Figure 3.4.3).

Interpretation

The leading causes of death shift as children grow into youth. For Canadian children age 1–9, the three leading causes of death in 2017 were unintentional injuries, cancer, and congenital anomalies (i.e., birth defects). For youth age 10–19, the leading causes of death in 2017 were unintentional injuries, suicide, and cancer.9

Preventable mortality

The Preventable Mortality section contains data on avoidable deaths in Middlesex-London from 2006 to 2015. Among those age 0–19, injuries and infection were the two leading causes of preventable death in Middlesex-London from 2013 to 2015 (Figure 3.5.6).

The Potential Years of Life Lost section contains data on the potential years of life lost (PYLL) for the Middlesex-London population under the age of 75. For those age 0–19, injuries and infection were the two leading causes of potential years of life lost due to preventable causes in 2013–2015 (Figure 3.6.6).

Interpretation

Deaths from preventable causes are deaths that might have been avoided through public health efforts such as vaccinations, injury prevention, or behavioural lifestyle change (e.g., quitting smoking).10 For example, interventions such as car seat regulations for children and mandatory helmet-use laws for cyclists under age 18, have been aimed at decreasing the incidence of injuries among children and youth. Student immunization programs are aimed at preventing the incidence of infections such as polio, measles, human papillomavirus (HPV) and tetanus among children and youth age 4–17 and beyond.11 Health promotion activities such as plain packaging requirements for tobacco are aimed at preventing smoking and encourage smoking cessation among youth. Preventable deaths are thus an indicator of the effectiveness of public health and health care systems in reducing deaths from preventable diseases and injuries.12

Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

References:

1. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 30]. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/d...

2. Statistics Canada. Healthy People, Healthy Places [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada, 2010 [cited 2019 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-229-x/82-229-x2009001-eng.pdf

3. Ganna A, Ingelsson E. 5 Year Mortality Predictors in 498,103 UK Biobank Participants: A Prospective Population-Based Study. Lancet [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Jul 29];386(9993):533–40. Available from: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(15)60175-1/fulltext DOI: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60175-1

4. Stenholm S, Kivimaki M, Jylha M, Kawachi I, Westerlund H, Pentti J, et al. Trajectories of Self-Rated Health in the Last 15 Years of Life by Cause of Death. Eur J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Jul 29];31(2):177–85. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10654-015-0071-0 DOI: 10.1007/s10654-015-0071-0

5. Berra S, Borrell C, Rajmil L, Estrada M-D, Rodríguez M, Riley AW, et al. Perceived Health Status and Use of Healthcare Services among Children and Adolescents. Eur J Public Health [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2019 Jul 29];16(4):405–14. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckl055 DOI: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl055

6. Forrest CB, Riley AW, Vivier PM, Gordon NP, Starfield B. Predictors of Children's Healthcare Use: The Value of Child Versus Parental Perspectives on Healthcare Needs. Med Care [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2019 Jul 29];42(3):232–8. Available from: https://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-prim...

7. Davison C, Michaelson V, Pickett W. It Still Takes a Village: An Epidemiological Study of the Role of Social Supports in Understanding Unexpected Health States in Young People. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2019 Jul 29];15:295. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4392631/ DOI: 10.1186/s12889-015-1636-2

8. Shumanty R. Report on the Demographic Situation in Canada - Mortality: Overview, 2014 to 2016 [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada, 2018 [cited 2019 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/91-209-x/2018001/article/54957-en...

9. Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0394-01 Leading Causes of Death, Total Population, by Age Group [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; 2019 [cited 2019 Jul 23]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/cv.action?pid=1310039401

10. Canadian Institute for Health Information. Avoidable Deaths [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2019 [cited 2019 Aug 8]. Available from: https://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/hsp/inbrief?lang=en#!/indicators/012/av...

11. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Vaccines for Children at School [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2015 [cited 2019 July 16]. Available from: https://www.ontario.ca/page/vaccines-children-school

12. OECD/European Union. Avoidable Mortality (Preventable and Amenable). In: Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle [Internet]. Brussels: OECD Publishing, Paris/European Union. 2018 [cited 2019 Aug 8]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/health_glance_eur-2018-35-en.pdf....

Last modified on: November 7, 2019

Jargon Explained

Self-perceived health

Population age 12 and over who rated their own health as either “excellent” or “very good” when asked, “In general, how would you say your health is: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?”

Self-perceived mental health

Population age 12 and over who reported perceiving their own mental health status as being “excellent” or “very good” when asked, “In general, would you say your mental health is: excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?"

Community belonging

Percent of the population age 12 and over who describe their sense of belonging as “very strong”, “somewhat strong”, “somewhat weak” or “very weak” (excludes “Don’t know” responses).

Preventable mortality

Refers to deaths from causes that can be potentially avoided by preventing a disease from developing. This includes deaths from conditions linked to modifiable risk factors, such smoking or excessive alcohol consumption (e.g., lung cancer, liver cirrhosis), and deaths linked to effective public health interventions (e.g., vaccinations, traffic safety legislation).

Potential years of life lost (PYLL)

The sum of the total years of life lost relative to age 75. PYLL is calculated by adding together, for all deaths, the number of years remaining until age 75, and then dividing this by the population under the age of 75 years.