Alcohol Use

Alcohol Use

The Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction (CCSA) recommends moderate drinking, if alcohol is consumed. Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines (LRADG) were introduced in 2011, providing specific information about the amount and frequency of alcohol drinking to reduce related acute and chronic harms.1 Nearly half the population exceeded either one or both of Canada’s Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines (LRADG) for chronic illness or binge drinking in 2015/16.1 The rate of drinking behaviour connected with chronic illness was lower at about one in four. This compares to nearly half of the population at risk of acute injury or poisoning from alcohol by binge drinking. Younger adults (age 20–44), males, those who had a job and those with the highest income levels had higher rates of exceeding the LRDAG and heavy drinking compared to their counterparts.

| Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines | Heavy Drinking |

| Binge Drinking |

Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines

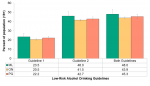

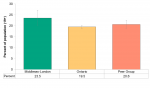

About a half (48.0%) of the population of legal drinking age in Middlesex-London reported exceeding the LRADGs in 2015/16. 23.5% of population aged 19 and older reported drinking at a level exceeding Guideline 1 (chronic disease) and 46.0% exceeded Guideline 2 (injury and poisoning risk) in the same time frame. While the proportions were slightly higher in Middlesex-London compared to Ontario and the Peer Group comparators, the differences were not statistically significant (Figure 5.2.1).

No significant differences were seen between urban and rural populations or by education level (not shown).

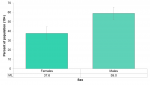

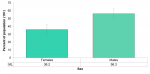

Nearly double the proportion of males (59.0%) exceeded the LRADGs compared to females (37.6%) in Middlesex-London in 2015/16. The difference was statistically significant (Figure 5.2.2).

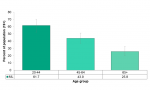

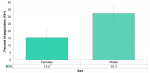

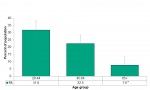

There was a downward trend in the percent of population exceeding the LRADGs as age increased. The differences between each age group were statistically significantly. Those in the youngest age group of 20–44 had the highest rate (61.7%) of exceeding compared to the 45–64 age group (43.9%) and compared to the age group 65 years and older (25.8%) (Figure 5.2.3).

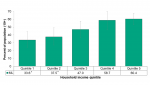

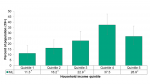

The proportion of the population aged 19 and older exceeding the LRADGs increased as household income increased in Middlesex-London in 2015/16. In the lowest household income quintile (Q1) 33.6% exceeded the guidelines compared to highest income quintile (Q5) where the percent was nearly double (60.4%). This is a statistically significant difference (Figure 5.2.4).

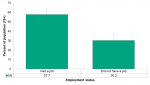

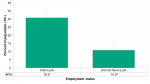

The proportion of the Middlesex-London population aged 19 and older who had a job and exceeded the LRADGs (57.7%) was nearly double that of those who did not have a job (30.2%). The difference was statistically significant (Figure 5.2.5).

Interpretation

Adherence to the LRADGs are important to reduce the risk of both long term chronic health impacts and acute harms from alcohol. Research has found that there would be nearly 4,600 fewer alcohol-related deaths if all Canadians followed the LRADGs.2 A large US study examining drinking behaviours found that those with drinking patterns similar to those who would be classified as drinking in excess of the Canadian LRADG had more than double the rate of fall-related injury compared to those who did not drink. This was true of all fall-related injuries as well as leisure and sports-related injuries.3

Middlesex-London had higher rates of exceeding the LRADGs in the younger age groups, males, urban populations and the highest household income quintile. These findings are consistent with results from a large cohort study in Alberta.4

Binge Drinking

Males (56.3%) had a much higher proportion of binge drinking (defined for males as drinking more than four drinks on one occasion in the past year) than females (36.3%). For females, binge drinking is defined as drinking more than three drinks on one occasion in the past year. The difference was statistically significant (Figure 5.2.6).

Heavy Drinking

Overall, 23.5% of the population reported monthly heavy drinking or drinking five or more drinks on one occasion at least once in the past month in Middlesex-London. While the rate is higher in Middlesex-London, there were no significant differences between Middlesex-London, Peer Group and Ontario (Figure 5.2.7).

Males had a significantly higher proportion of heavy drinking (32.3%), defined as five or more drinks on one occasion monthly, compared to females (15.5%) in Middlesex-London in 2015/16 (Figure 5.2.8).

In 2015/16, the proportion of people who reported heavy drinking decreased significantly as age increased. Those in the 20–44 age group reported a heavy drinking rate of 31.8% compared to 7.6% in those aged 65 and older (Figure 5.2.9).

Generally, there was an upward trend in the proportion who reported heavy drinking as household income increased. Those in the lowest income quintile (11.3%) had a significantly lower proportion than those in the two highest income quintiles (37.5 for Q4 and 26.9% for Q5) (Figure 5.2.10).

Those who had a job reported monthly heavy drinking three times as often (30.8%) as those who did not have a job (10.9%). The difference was statistically significant (Figure 5.2.11).

There were no significant differences seen between urban and rural populations or by education level for heavy drinking (not shown).

Interpretation

Despite those in the highest income quintiles reporting higher rates of heavy and binge drinking and generally drinking more than the recommendations in guidelines, these groups experience fewer acute and chronic health conditions compared to those in the lowest income quintile. Research shows that alcohol-related hospital admissions for conditions attributable to alcohol were significantly higher in males, compared to females. Admission rates in the most deprived socioeconomic groups were higher than the least deprived and the gap was wider for males than females. In Middlesex-London, health conditions fully attributable to alcohol had a significantly higher rate in the lowest socioeconomic group compared to highest group (Figure 2.6.5).

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

References:

1. Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. Canada’s low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction; 2018 [cited 2019 Mar 22]. 2 p. Available from: http://www.ccdus.ca/Resource%20Library/2012-Canada-Low-Risk-Alcohol-Drin...

2. Butt P, Beirness D, Gliksman L, Paradis C, Stockwell T. Alcohol and health in Canada: A summary of evidence and guidelines for low risk drinking. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse [Internet]. 2011 Nov 25 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. Available from: http://www.ccdus.ca/Resource%20Library/2011-Summary-of-Evidence-and-Guid...

3. Chen CM, Yoon Y-H. Usual alcohol consumption and risks for nonfatal fall injuries in the United States: results from the 2004–2013 National Health Interview Survey. Subst Use Misuse [Internet]. 2017 Sep [cited 2019 Mar 22];52(9):1120–32. Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10826084.2017.1293101?journa...

4. Brenner DR, Haig TR, Poirier AE, Akawung A, Friedenreich CM, Robson PJ. Alcohol consumption and low-risk drinking guidelines among adults: a cross-sectional analysis from Alberta’s Tomorrow Project. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can [Internet]. 2017 Dec [cited 2019 Mar 22];37(12):413–24. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publicati...

5. Green MA, Strong M, Conway L, Maheswaran R. Trends in alcohol-related admissions to hospital by age, sex and socioeconomic deprivation in England, 2002/03 to 2013/14. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2017 May 8 [cited 2019 Mar 22];17(1):Article 412 [about 15 p.]. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-017-42...

Last modified on: May 7, 2019

Jargon Explained

Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines

Exceeding the low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines means drinking in excess of the recommendations in either guideline 1 or guideline 2.

Guideline 1

To reduce long term harm. Recommends no more than 10 standard drinks a week for women (no more than 2 a day) and no more than 15 standard drinks a week for men (no more than 3 a day). Include non-drinking days.

Guideline 2

To reduce risk of injury. Recommends drinking no more than 3 standard drinks a day for women or 4 for men on any single occasion.

Binge drinking

For women this means drinking more than 3 standard drinks and for men more than 4 standard drinks on any single occasion in the past year. This is also the same as drinking in excess of the recommendations of Guideline 2 of the Low-Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines.

Heavy drinking

Monthly occurrences of drinking 5 or more standard drinks on any single occasion.

Standard Drink Size

A standard drink is 13.6 g of alcohol, which translates into 5 oz of 12% wine, 1.5 oz of 40% distilled alcohol (rye, gin, rum, etc.), or 12 oz of 5% beer.