Indigenous Population

Indigenous Population

Indigenous people lived in this area long before the arrival of the first settlers. Middlesex-London Health Unit is located on the traditional lands of the Attawandaran (neutral) peoples who once settled this region alongside the Algonquin and Haudenosaunee peoples.1 The three First Nations communities with longstanding ties to this area are: Chippewa of the Thames First Nation (Anishinaabe); Oneida Nation of the Thames (Haudenosaunee); and Munsee-Delaware Nation (Leni-Lunaape).

About 2.5% (11,145) of the population in Middlesex-London identified themselves as Indigenous (i.e., First Nations, Métis and Inuit) on the 2016 Census.2 They were largely urban Indigenous people that reside in the urban population centres. The census counts included the First Nation community of Munsee-Delaware Nation (population 153) but did not include the other two larger First Nation Communities that neighbour the health unit. These communities chose not to participate in the 2016 Census.

Overall the percent of the population self-identifying as Indigenous on the census in 2016 was similar to the percent in 2011 (9,860; 2.3%)3 and similar to Ontario overall in 2016 (2.8%) but lower than Canada as a whole in 2016 (4.9%).4

The number of Indigenous people in Middlesex-London is likely much higher than the Census indicates. In 2016, the Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre (SOAHAC) led a community-based research project, Our Health Counts London5, which indicated that there could be as many as 17,108 to 22,155 Indigenous adults who live, work or access services in London.6 It is important to consider the census data in the context of other sources of data such as Our Health Counts London to gain a more complete picture of the population.

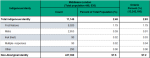

According to the 2016 Census, the majority (72%; 8,020) of Indigenous people in Middlesex-London identified as First Nations followed by Métis (23.8%; 2,655) (Figure 1.6.1). Our Health Counts London also identified that the majority of Indigenous adults in London were First Nations and that First Nations people comprised a much higher percent of the Indigenous population (95%).6

A higher percent of the Indigenous population in Middlesex-London were children (i.e., aged 0-14, 25.4%; 2,835) compared with seniors (i.e., aged 65 and older, 16.3%, 715) on the 2016 Census.7 This is consistent with the general picture suggested in Our Health Counts London which indicated there was a greater percent of the Indigenous population in younger age groups.8 It contrasts with the change happening within the non-Indigenous or settler population, where 2016 marked a milestone shift to a higher proportion of seniors overall compared with children (aged 14 and younger) in Middlesex-London and Ontario.9

Within the First Nations population, the majority, 60.3% (4,840), had Registered or Treaty Indian status, as defined under the Indian Act, according to the 2016 Census.7 Our Health Counts London also found that the majority of First Nations adults had federal Indian status in London and that those that had Registered or Treaty Indian status comprised a much higher percent (98%).6 This may be due to a greater participation of those with federal Indian Status in the Our Health Counts London as First Nations communities were incompletely enumerated in the census.

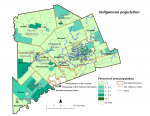

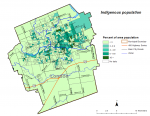

Maps indicated Indigenous people were generally dispersed throughout Middlesex London (Figure 1.6.2) and the City of London (Figure 1.6.3) with some specific areas of concentration. Areas where a higher proportion of people who self-identified as Indigenous lived, included: Southwest Middlesex, Strathroy Caradoc and the City of London, particularly the northeast of London. Data is missing for the neighbouring First Nation communities, but people that lived in these areas may be understood to be almost entirely First Nations.

Interpretive Notes

Public health endeavours to build partnerships with Indigenous communities to address disparities in health outcomes and reduce health inequities.10

Statistics Canada indicated that across Canada more people are newly identifying as Indigenous on the Census.4 However, the population counts should be interpreted with caution as the Census generally continues to underrepresent Indigenous populations. In 2016, the Chippewas of the Thames First Nation and the Oneida Nation of the Thames band councils did not give Statistics Canada permission to enter their territory and did not participate in the Census. In addition, less than 50 percent of the members of Munsee-Delaware Nation completed the more detailed questions such as age group. For these reasons, which are likely rooted in a distrust of government due to past and present colonial policies10, there is an undercounting of Indigenous people and in particular an undercounting of those with Registered or Treaty Indian status.

A 2016 urban Indigenous health study led by the Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre (SOAHAC), Our Health Counts London, indicated that only 14% of Indigenous adults in London completed the 2011 Census and that the Indigenous population is likely three to four times higher more than that estimated by Statistics Canada.5 More detailed urban Indigenous health status information, including demographic information is available on the SOAHAC website.

Indigenous identity is based on Statistics Canada's “Aboriginal identity” derived variable which includes persons who are First Nations (North American Indian), Métis or Inuk (Inuit) and/or those who are Registered or Treaty Indians (that is, registered under the Indian Act of Canada) and/or those who have membership in a First Nation or Indian band. Aboriginal peoples of Canada are defined in the Constitution Act, 1982, section 35 (2) as including the Indian, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada

Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability

Population Health Assessment and Surveillance Protocol, 2018

References:

- Ontario Federation of Labour Aboriginal Circle and Ontario Federation of Labour Aboriginal Persons Caucus. Traditional Territory Acknowledgements in Ontario [Internet]. Toronto ON: Ontario Federation of Labour 2017 [cited 2018 Nov 22]. Available from: www.ofl.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017.05.31-Traditional-Territory-Acknowledgement-in-Ont.pdf

- Statistics Canada. Middlesex, CTY [Census division], Ontario (table). Aboriginal Population Profile. 2016 Census Catalogue no. 98-510-X2016001 [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada; [updated 2018 Jul 18; cited 2018 Nov 27] Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016

- Statistics Canada. Middlesex, CTY, Ontario (Code 3539) (table). National Household Survey (NHS) Aboriginal Population Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-011-X2011007 [Internet]. Ottawa. ON 2013: Statistics Canada, [updated 2013 Nov 13; cited 2018 Dec 3] Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca

- Statistics Canada. The Daily- Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: Statistics Canada. 2017 [updated 2017 Oct 25; cited 2018 Dec 3] Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/171025/dq171025a-eng.htm

- Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre [Internet]. London, ON. Our health counts London, ca 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 27] Available from: http://soahac.on.ca/our-health-counts

- Firestone M, Xavier C, O’Brien K, Maddox R, Muise GM, Dokis B, Smylie J. Our health counts London [Internet]. London (ON): Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre; 2018. Adult demographics; [cited 2018 Nov 27]; [3 p.]. Available from: http://soahac.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/OHC-02A-Adult-Demographics-2.pdf

- Statistics Canada. Focus on Geography Series, 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-404-X2016001. Ottawa, ON. 2017. [updated 2017 Apr 23; cited 2018 Dec 3) https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/as-sa/fogs-spg/Facts-cd-eng.cfm?LANG=Eng&GK=CD&GC=3539&TOPIC=9

- Firestone M, Xavier C, O’Brien K, Raglan M, Muise GM, Dokis B, Smylie J. Our health counts London [Internet]. London (ON): Southwest Ontario Aboriginal Health Access Centre; 2018. Child demographics; [cited 2018 Nov 27]; [1 p.]. Available from: http://soahac.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/OHC-02B-Child-Demographics-1.pdf

- Statistics Canada. 2017. Middlesex-London Health Unit, [Health region, December 2017], Ontario and Ontario [Province] (table). Census Profile. 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001. Ottawa, ON 2017: Statistics Canada. [Updated 2017 Nov 29; cited 2018 Nov 27] Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca

- Ontario. Population and Public Health Division, Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Relationships with Indigenous Communities Guideline. 2018.Toronto, ON: Queen’s Printer for Ontario; 2018. Available from: http://health.gov.on.ca

Last modified on: January 25, 2019

Jargon Explained

Indigenous

A collective name for the original peoples of North America (i.e., First Nations, Métis and Inuit) and their descendants. The indicator “Aboriginal peoples” is used on the 2016 Census to determine Indigenous identity that is, North American Indian, Métis or Inuit, and/or those who reported being a Treaty Indian or a Registered Indian, as defined by the Indian Act of Canada, and/or those who reported they were members of an Indian band or First Nations. The Canadian Constitution recognizes three groups of Aboriginal people — Indians, Métis and Inuit. These are three separate peoples with unique heritages, languages, cultural practices and spiritual beliefs.

Treaty Indian

A First Nations person with status under the Indian Act, that signed a treaty with the Crown, or a person of Aboriginal ancestry who holds treaty status under the Federal Indian Act.