Early development

Early development

Ontario public health units have a mandate to support the healthy growth and development of children in the province, which includes the physical, mental, emotional and social well-being of a child.1 A wide range of programs and services exist in Ontario to support healthy growth and development from birth to the age of six (and beyond). Screening with the Healthy Babies Healthy Children (HBHC) postpartum tool has found that a higher percent of babies in Middlesex-London have families in need of newcomer support, concerns about money, and with a parent who has a history of mental illness, compared to Ontario. At eighteen months of age—a milestone in a child’s development—a higher percent of children in Middlesex-London saw a healthcare provider for an 18-month well-baby visit compared to Ontario. For kindergarten age children in Middlesex-London, their ability to meet age-appropriate development expectations in five general domains has been fairly similar to other children across Ontario, as measured by four cycles of the Early Development Instrument.

| Risk factors for healthy child development | Early Development Instrument |

| Enhanced 18-month well-baby visits |

Risk factors for healthy child development

The percent of infants screened with the HBHC postpartum tool in Middlesex-London with a mother as a single parent was 4.3% in 2018, down from 10.3% in 2015 (Fig. 12.3.1). From 2015 to 2017, the only years for which Ontario data are available, the percent in Middlesex-London was significantly higher compared to Ontario.

In Middlesex-London, 5.4% of infants screened with the HBHC postpartum tool in 2018 did not have a designated primary care provider for the mother or the infant, down from 8.2% in 2015 (Fig. 12.3.2). From 2015 to 2017, the percent in Middlesex-London was significantly higher compared to Ontario.

In Middlesex-London, 3.4% of infants screened with the HBHC postpartum tool in 2018 had a mother who did not have an Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) number, more than double the percent in 2017 (1.6%) (Fig. 12.3.3). In 2017, the most recent year for which Ontario data are available, the percent in Middlesex-London was significantly lower compared to Ontario (1.6% and 2.8%, respectively).

The percent of infants screened with the HBHC postpartum tool in Middlesex-London with a family in need of newcomer support was 8.3% in 2018, up from 6.2% in 2015 (Fig. 12.3.4). From 2015 to 2017, the percent in Middlesex-London was significantly higher compared to Ontario and the Peer Group, and among the highest in the province.

In Middlesex-London, 7.6% of infants screened with the HBHC postpartum tool in 2018 had a parent who had concerns about money to pay for housing/rent and the family’s food, clothing, utilities and other basic necessities (Fig. 12.3.5). From 2015 to 2017, the percent in Middlesex-London was significantly higher compared to Ontario.

The percent of infants screened with the HBHC postpartum tool in Middlesex-London with a parent that had a history of depression, anxiety, or mental illness was 26.3% in 2018, down from 31.0% in 2016 (Fig. 12.3.6). From 2015 to 2017, the percent in Middlesex-London was significantly higher compared to Ontario.

The percent of infants screened with the HBHC postpartum tool in Middlesex-London with a parent that had a disability that may impact parenting was 1.0% in 2018, down from 1.8% in 2015 (Fig. 12.3.7). The percent in Middlesex-London was 1.2% in 2017, which was not significantly different compared to Ontario (1.0%).

The percent of infants screened with the HBHC postpartum tool in Middlesex-London with a parent who had been involved with Child Protection Services was 4.2% in 2018, down from 6.9% in 2016 (Fig. 12.3.8). From 2015 to 2017, the percent in Middlesex-London was significantly higher compared to Ontario.

Interpretation:

The Healthy Babies Healthy Children (HBHC) program is designed to help children in Ontario have a healthy start in life. The program is funded by the Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services and delivered through Ontario’s public health units in partnership with hospitals and other community partners.2 It is a free and voluntary program available to pregnant women and families with children up to the age of six.3 The program includes screening to identify families with potential risk factors that could impact a child’s healthy development, home visits by Public Health Nurses and trained Family Visitors, service coordination (where needed), and referrals to a variety of community programs and services based on where additional support(s) may be needed.4

The HBHC screen is intended to identify families experiencing challenges who may benefit from the HBHC home-visiting program during the prenatal, postpartum, or early childhood periods. The screening tool is completed by a healthcare provider (e.g., registered nurse, midwife, physician) with consent from the infant’s mother. It includes 36 questions about the pregnancy and birth, the family, parenting, infant development and healthcare professional observations. To identify families that may benefit from the program, the tool considers certain risk factors for healthy child development, such as: infant’s mother is a single parent, no designated primary care provider for the mother and child, mother does not have an Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) number, family is in need of newcomer support, family has concerns about money, parent or partner has a history of mental illness, parent or partner has a disability that may impact parenting, and parental involvement with Child Protection Services.

Stress is a factor that shapes the brain architecture in a developing child. Some stress is normal and is healthy for a child’s development as it prepares them for responding to larger challenges in the future.5 However, exposure to strong, frequent, and/or prolonged stress—such as chronic neglect or abuse, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness, or the impacts of poverty—increases the likelihood of lifelong problems in learning, behaviour, and physical and mental health. In situations where such stressors are likely, intervening early can prevent, mitigate, or reverse the damaging effects of the stressors, and thus set up children for greater success throughout life.6

The HBHC program recognizes that every family has strengths. Public Health Nurses and Family Home Visitors support families to identify, leverage, and build on their strengths.

Enhanced 18-month well-baby visits

The percent of children in Middlesex-London that had an enhanced 18-month well-baby visit was 64.4% in 2016, a percent significantly higher compared to Ontario (57.3%) and the Peer Group (58.2%) (Fig. 12.3.9). In Middlesex-London, the percent increased over time from 2010 (50.7%) to 2016 (64.4%).

Interpretation:

In October 2009, the Ontario government introduced new code fees as an incentive for primary care physicians to conduct the Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit. The longer and more in-depth visit includes the use of standardized tools and promotes increased communication between parents and physicians (or other health professionals) on child development, parenting, early literacy, and local community resources that promote healthy learning, reading and age-appropriate play.7, 8 Ontario public health units help to promote awareness about the enhanced 18-month well-baby visit and its value in supporting a child’s healthy growth and development.

The Early Development Instrument

For each of the five domains of the Early Development Instrument (EDI), children with scores below the 10th percentile cut-off of the Ontario Baseline population are considered vulnerable.

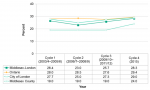

In cycle 4 (2015), 17.0% of children in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on the Physical Health and Well-being domain, compared to 16.1% in Ontario (Fig. 12.3.10). For Middlesex-London, the percent increased over time between cycles 2 (12.0%) and 4 (17.0%). In each of the EDI cycles, a higher percent of males in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on this domain compared to females (figure not shown).

Across all cycles of the EDI, the percent of children in Middlesex-London who were vulnerable on the Social Competence domain was slightly lower compared to Ontario (Fig. 12.3.11). For Middlesex-London, the percent increased over time between cycles 2 (6.6%) and 4 (10.2%). In each of the EDI cycles, a higher percent of males in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on this domain compared to females (figure not shown).

In cycle 4 (2015), 12.6% of children in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on the Emotional Maturity domain, compared to 10.3% in Ontario (Fig. 12.3.12). For Middlesex-London, the percent increased over time between cycles 2 (8.6%) and 4 (12.6%). In each of the EDI cycles, a much higher percent of males in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on this domain compared to females (figure not shown).

In cycle 4 (2015), 5.8% of children in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on the Language and Cognitive Development domain, compared to 9.6% in Ontario (Fig. 12.3.13). For Middlesex-London, the percent decreased over time between cycles 1 (8.5%) and 4 (5.8%). In each of the EDI cycles, a higher percent of males in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on this domain compared to females (figure not shown).

In cycle 4 (2015), 9.4% of children in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on the Communication Skills and General Knowledge domain, compared to 12.1% in Ontario (Fig. 12.3.14). For Middlesex-London, the percent decreased over time between cycles 1 (10.6%) and 4 (9.4%). In each of the EDI cycles, a higher percent of males in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on this domain compared to females (figure not shown).

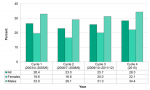

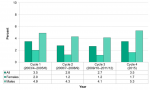

Overall, 28.3% of children in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on at least one domain in Cycle 4, a lower percent compared to Ontario (29.4%) (Fig. 12.3.15). For Middlesex-London, the percent increased over time between cycles 2 (2006/7–2008/9) and 4 (2015). In each of the cycles, the percent of children vulnerable was higher in the City of London compared to Middlesex County.

In each of the EDI cycles, a higher percent of males in Middlesex-London were vulnerable on a least one domain compared to females (Fig. 12.3.16). For example, in Cycle 4, 34.4% of males were vulnerable compared to 22.1% of females.

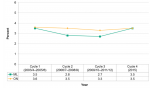

Children with scores below expectations on nine or more of the 16 subdomains are considered to have multiple challenges. In Cycle 4, 3.5% of children in Middlesex-London had multiple challenges, the same percentage as Ontario (Fig. 12.3.17). While the percent remained relatively stable in Ontario across the four cycles, a relatively large increase was observed in Middlesex-London for Cycle 4 compared to the previous two cycles.

In each of the EDI cycles, a higher percent of males in Middlesex-London had multiple challenges compared to females (Fig. 12.3.18). For example, in Cycle 4, 5.3% of males were considered to have multiple challenges compared to 1.7% of females.

Interpretation:

The Early Development Instrument (EDI) is a questionnaire developed by the Offord Centre for Child Studies at McMaster University. The questionnaire is designed to assess children’s ability to meet age-appropriate developmental expectations in five general domains: 1. physical health and well-being, 2. social competence, 3. emotional maturity, 4. language and cognitive development, and 5. communication skills and general knowledge.9

The questionnaire is completed by kindergarten teachers for each student in their senior kindergarten class. The results are then grouped together to give a picture of how children are doing across neighbourhoods, cities, or other population level.9 The EDI provides population-level data that can help communities monitor the developmental health and well-being of children within their boundaries, and to deliver programs and services that address local needs.10

Figure 12.3.15: Children vulnerable on at least one domain of the Early Development Instrument (EDI)

Healthy Growth and Development Guideline, 2018

Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability

References:

1. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Healthy Growth and Development Guideline, 2018 [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 26]. Available from: http://health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/...

2. Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). Healthy Babies Healthy Children Process Implementation Evaluation: Executive Summary [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2014 [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/hbhc-exec.pdf?la=en

3. Ministry of Children Community and Social Services. Healthy Babies Healthy Children [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2016 [cited 2019 Mar 21]. Available from: http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/english/earlychildhood/health/index...

4. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Postpartum Implementation Guidelines for the Healthy Babies, Healthy Children Program [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2001 [cited. Available from: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/english/providers/pub/child/hbabies/postpart...

5. Alberta Family Wellness Initiative. Stress: How Positive, Tolerable, and Toxic Stress Impact the Developing Brain [Internet]. Calgary, Alberta: Palix Foundation; 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 29]. Available from: https://www.albertafamilywellness.org/what-we-know/stress

6. Center on the Developing Child. InBrief: The Science of Early Childhood Development [Internet]. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard Unversity; 2017 [cited 2019 Mar 25]. Available from: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/inbrief-science-of-ecd/

7. Ministry of Children Community and Social Services. Ontario's Enhanced 18-Month Well-Baby Visit: Information for Physicians & Other Health Professionals [Internet]. Toronto: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2015 [cited 2019 Mar 26]. Available from: http://www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/earlychildhood/health/enhan...

8. Guttman A, Cairney J, MacCon K, Kumar M. Uptake of Ontario's Enhanced 18-Month Well Baby Visit [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, 2016 [cited 2019 Mar 26]. Available from: https://www.ices.on.ca/Publications/Atlases-and-Reports/2016/Well-Baby

9. Offord Centre for Child Studies. EDI in Ontario over Time [Internet]. Hamilton, ON: McMaster University, 2018 [cited 2019 Mar 26]. Available from: https://edi.offordcentre.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/EDI-in-Ontari...

10. Janus M, Offord DR. Development and Psychometric Properties of the Early Development Instrument (EDI): A Measure of Children's School Readiness. Can J Behav Sci [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2019 Mar 21];39(1):1-22. Available from: https://edi.offordcentre.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Janus-Offord-... DOI: 10.1037/cjbs2007001

Last modified on: May 7, 2019

Jargon Explained

HBHC prenatal period

From conception up to the birth of the infant.

HBHC postpartum period

From the infant’s birth up to six weeks of age.

HBHC early childhood period

From six weeks of age to six years of age.

Client or family in need of newcomer support

A client or family who is new to Canada (less than five years living in Canada), who lacks social supports, or who may be experiencing social isolation.

Infant’s mother is a single parent

A mother who identifies herself as the sole primary caregiver for the baby/child.

Parent or partner has a history of mental illness

A mother, father or parenting partner has a history of depression, anxiety or other mental illness.

Infants with family involved with Child Protection Services

Includes families with past or present involvement with Child Protection Services. Excludes involvement of parents with Child Protection Services when they were children.

Physical Health & Well-being domain

Assesses children’s physical readiness for the school day, their physical independence, and their gross and fine motor skills.

Social Competence domain

Assesses children’s readiness to explore new things, their approaches to learning, the amount of responsibility and respect they show, and their overall social competence.

Emotional Maturity domain

Assesses children’s prosocial and helping behaviour, their anxious and fearful behaviour, their aggressive behaviour, and their amount of hyperactivity and inattentive behaviour.

Language & Cognitive Development domain

Assesses children’s basic and advanced literacy skills, their basic numeracy skills, their interest in reading and math, and their ability to remember things.

Communication Skills & General Knowledge domain

Assesses children’s ability to communicate in socially appropriate ways, their use of language, their ability to tell a story, and their knowledge about the world around them.

Percent of children with multiple challenges

The percent of children with scores below expectations on nine or more of the 16 subdomains of the Early Development Instrument (EDI).

Percent of children vulnerable in a domain

The percent of children who scored below the 10th percentile cut-off of the Ontario Baseline population in a particular domain of the Early Development Instrument (EDI). It indicates the percent of children who are struggling in a particular domain compared to the Ontario Baseline data.