Birth outcomes

Birth outcomes

Births are a key component of population growth and an indicator of the reproductive capacity of a population. Ontario public health units have a mandate to support preconception health and healthy pregnancies, and prevent adverse birth outcomes such as low birth weight, preterm births, and birth defects or other complications.1 In Middlesex-London, approximately 4500 to 4900 babies were born each year between 2006 and 2017. Most of these babies were born within a healthy range for birth weight, size and gestational age. The rate of babies born with a birth defect decreased significantly since 2013, to become similar to those seen across Ontario. Stillbirth rates have consistently been higher than those seen across Ontario. In general, women in Middlesex-London are having their first baby at an older age and having fewer babies overall, a trend also seen across Ontario.

| Birth counts and rates | Birth weight for gestational age |

| Sex ratio at birth | Stillbirths |

| Multiple births | Congenital anomalies |

| Preterm births | Average age of mother at birth of first infant |

| Birth weight |

Birth counts and rates

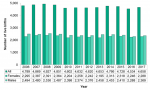

The annual number of live births in Middlesex-London ranged between 4,534 and 4,927 from 2006 to 2017, for an average of approximately 4,700 babies per year. During each of these years, slightly more male babies were born than female babies (Fig. 12.1.1).

The annual number of live births among the rural population of Middlesex-London ranged between 511 and 572 (Fig. 12.1.2) from 2006 to 2017. On average, rural births made up 11.4% of live births in Middlesex-London each year.

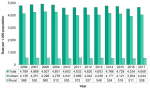

The birth rates in Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group saw a gradual decline from 2006 to 2017. During this period, the birth rate in Middlesex-London was similar to Ontario but slightly higher than the Peer Group (Fig. 12.1.3).

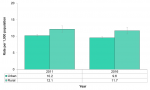

In Middlesex-London, the birth rate was significantly higher in the rural population compared to the urban population in 2011 and 2016. In 2016, the birth rate for the rural population was 11.7 per 1,000 population compared to 9.6 per 1,000 population in the urban population (Fig. 12.1.4).

While the birth rates for both populations decreased from 2011 to 2016, the decrease was smaller in the rural population (-3.3%) compared to the urban population (-5.9%).

Interpretation:

The birth rate is the annual number of live births in a given population per 1,000 people. It is influenced by the age structure of the population.2 For example, a population with a high percentage of women of reproductive age (15 to 49 years) will generally have a higher birth rate; whereas, a population with an older age structure will generally have a lower birth rate.

Data related to birth counts and rates can be useful for planning purposes to local government bodies and organizations that provide education, healthcare and other social services to the community.

Sex ratio at birth

The sex ratio at birth for Middlesex-London varied between 101.9 and 112.0 from 2006 to 2017, for an average of 105.9 (Figure 12.1.5). In 2013, the sex ratio for Middlesex-London was significantly higher than Ontario. For all other years during this period, the annual sex ratio for Middlesex-London was not significantly different from Ontario or the Peer Group.

Interpretation:

Sex ratio at birth is the number of male births divided by the number of female births.

Around the world, the natural sex ratio at birth is around 105; that is, there are approximately 105 males born for every 100 females.3 With time, the sex ratio of a population is expected to equalize since males are at a higher risk of dying at a younger age compared to females.3

Multiple births

There were 3.2 multiple births per 100 live births in Middlesex-London in 2017. The percent of multiple births remained relatively steady from 2006 to 2017 for Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group. The larger fluctuations seen with the Middlesex-London data are expected based on the relatively small numbers of multiple births (Fig. 12.1.6).

Interpretation:

A multiple birth occurs when a mother delivers two or more infants from the same pregnancy. It is associated with a higher risk of complications for both the mother and babies compared to a singleton birth.

Mothers carrying multiples are more likely to have gestational diabetes, hypertension, pre-eclampsia, miscarriages, and Caesarian sections (C-sections). Babies of multiple births are more likely to be born prematurely and to have below-normal birth weights.4

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, women who have undergone fertility treatments are around 20 times more likely to have a multiple pregnancy than if they had become pregnant naturally.4

Preterm births

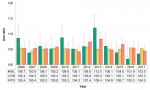

The rate of preterm births in Middlesex-London was 8.1 per 100 live births in 2017, a rate similar to Ontario. Between 2007 and 2017, rates over time were stable in Middlesex-London (Fig 12.1.7).

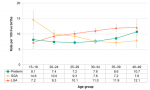

Preterm birth rates in Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group were highest for mothers age 45 to 49 and lowest for mothers age 25 to 29 between 2013 to 2017 (Fig. 12.1.8). The margin of error (95% confidence interval) is higher for some age groups—particularly among mothers age 45 to 49—due to the small number of women who gave birth in those age groups.

For Ontario, the preterm birth rate among mothers age 45 to 49 was significantly higher than other maternal age groups. For Middlesex-London, the differences across age groups are not statistically significant due to the small number of women in some of the age groups (i.e., 15 to 19, 40 to 44, 45 to 49) (Fig. 12.1.8).

Interpretation:

A normal pregnancy can range from 38 to 42 weeks. A preterm birth occurs when a baby is born before 37 weeks (or 259 days) of pregnancy have been completed.5 The earlier a baby is born, the higher the risk of serious complications for the baby.

Birth weight

The low birth weight rate in Middlesex-London was 5.9 per 100 live births in 2017; a rate significantly lower than Ontario. Between 2009 and 2017, rates in Middlesex-London were relatively stable and lower compared to Ontario; although the difference was only statistically significant in 2017 (Fig. 12.1.9).

The low birth weight rate among the urban population of Middlesex-London was 6.0 per 100 live births in 2017, compared to 4.8 in the rural population (not shown). From 2007 to 2017, rates were higher in the urban population compared to the rural population; although the differences were generally not statistically significant.

The high birth weight rate in Middlesex-London was 1.6 per 100 live births in 2017. Between 2006 and 2017, the rates for Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group were similar and were steady over time (Fig. 12.1.10).

The high birth weight rate among the urban population of Middlesex-London was 1.6 per 100 live births in 2017, compared to 1.9 in the rural population (not shown). From 2011 to 2017, the high birth weight rate was higher in the rural population compared to the urban population, although the differences were not statistically significant.

Interpretation:

A baby’s weight at birth is an important indicator of newborn and maternal health.6

A low birth weight is defined as a birth weight of less than 2,500 grams (5.5 pounds), regardless of the gestational age of the baby.7 The most common causes of low birth weight are preterm birth (before 37 weeks of pregnancy have been completed) and restricted fetal growth.8 A baby with a low birth weight has a higher risk of mortality9, and may have a harder time feeding, gaining weight, and fighting infection.10

A high birth weight is defined as a birth weight of 4,500 grams (9.9 pounds) or more, regardless of the gestational age of the baby.11 Mothers carrying high-weight fetuses have a higher risk of Caesarian sections 12, while babies with high birth weights have a higher risk of obesity later in life.13 Some babies can have a high birth weight because of genetics (their parents are big), the amount of weight their mother gained during pregnancy, or their mother had diabetes during pregnancy.14

Birth weight for gestational age

The rate of small for gestational (SGA) births in Middlesex-London was 8.4 per 100 live births in 2017. Compared to Ontario (9.7 per 100 live births), the rate in Middlesex-London was significantly lower (Fig. 12.1.11).

Rates of SGA births in Middlesex-London were relatively stable between 2006 and 2017, while those for Ontario increased slightly over time (Fig. 12.1.11).

The rate of SGA births among the urban population of Middlesex-London was 8.7 per 100 live births in 2017; a rate significantly higher compared to the rural population (5.5 per 100 live births). SGA birth rates were consistently higher among the urban population compared to the rural population from 2006 to 2017 (figure not shown).

The rate of large for gestational (LGA) births in Middlesex-London was 10.1 per 100 live births in 2017 (Fig. 12.1.12).

Rates of LGA births in Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group followed a similar pattern from 2006 to 2017. During this period, rates in Middlesex-London were not significantly different from Ontario or the Peer Group (Fig. 12.1.12).

LGA birth rates were consistently higher among the rural population of Middlesex-London compared to the urban population from 2006 to 2017; however, the differences were not statistically significant (figure not shown).

In Middlesex-London from 2013 to 2017, mothers age 15 to 19 had the highest small for gestational age (SGA) birth rates. SGA birth rates had an inverse relationship with maternal age; that is, the rates decreased as the mother’s age group increased (Fig. 12.1.13).

Similarly, mothers age 15 to 19 had the lowest large for gestational age (LGA) birth rates. LGA rates during this period increased with maternal age and were highest among mothers age 40 to 49 (Fig. 12.1.13).

Interpretation:

Birth weight for gestational age is a measure of fetal growth. It can be influenced by many different factors, including: ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gestational diabetes, maternal smoking, maternal height and weight, maternal weight gain during pregnancy, and the baby’s sex.15

While low birth weight is an important measure of birth outcome, it is important to consider it within the context of the baby’s gestational age and sex.16 For example, a baby delivered at 37 weeks is likely to have a low birth weight compared to a baby born at 40 weeks, but may not be undersized compared to other babies of the same gestational age and sex.

A baby is considered small for gestational age (SGA) if the birth weight falls below the tenth percentile based on a sex-specific, population-based Canadian reference standard at 22 to 43 completed weeks.17 The baby may be small because of genetics (parents are small) or because its growth was restricted by one or more factors during pregnancy. A baby that is SGA may have difficulty maintaining a normal body temperature, and have a higher risk of infection, decreased blood oxygen levels (perinatal asphyxia), and low blood sugar (hypoglycemia).18

A baby is considered large for gestational age (LGA) if the birth weight is above the ninetieth percentile based on a sex-specific, population-based Canadian reference standard at 22 to 43 completed weeks.17 The baby may be large because of genetics (parents are big), the amount of maternal weight gain during pregnancy, or due to gestational diabetes. A baby that is LGA has a higher risk of injuries at birth, low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), and a low Apgar score (infant’s clinical status in the first few minutes after birth).14

Stillbirths

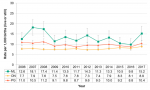

The stillbirth rate in Middlesex-London was 15.2 per 1,000 births in 2017, compared to 8.9 in Ontario and 10.4 in the Peer Group. Between 2006 and 2017, stillbirth rates in Middlesex-London were significantly higher than Ontario each year except for 2014 and 2015. The larger fluctuations seen with the Middlesex-London data are expected based on the relatively small number of stillbirths each year (Fig. 12.1.14).

Interpretation:

A stillbirth is the death of a fetus in the womb weighing 500 grams or more, or of 20 or more weeks of gestation.19 The stillbirth can happen during pregnancy or the birth process. Some stillbirths are linked to problems with the placenta and umbilical cord, birth defects or genetic problems with the fetus, or health conditions in the mother; however, often the specific cause of a stillbirth cannot be determined.20

Advances in technology have greatly improved the ability to detect birth defects or genetic problems with the fetus during pregnancy21, sometimes leading to the termination of an affected pregnancy. In Ontario, the termination of a pregnancy with a fetus weighing 500 grams or more, or of 20 or more weeks of gestation, is classified as a stillbirth.22 Increases in pregnancy terminations have been found to be responsible for increases in stillbirth rates and associated with declines in the rate of congenital anomalies in newborns.23

Congenital anomalies

The rate of births (live or still) in Middlesex-London with one or more confirmed congenital anomalies was 112.8 per 10,000 in 2017, compared to 110.7 in Ontario; a difference that is not statistically significant. Between 2013 and 2017, the rate in Middlesex-London decreased over time from 322.4 to 112.8 per 10,000 births (Fig. 12.1.15).

Interpretation:

Congenital anomalies are abnormalities in the baby at birth, such as Down syndrome, spina bifida, cleft palate and congenital heart defects. They are also known as birth defects or congenital malformations. The abnormality may be present from conception or develop during the pregnancy.24

Congenital anomalies can be caused by genetic, infectious, nutritional or environmental factors, but approximately 50% of all cases cannot be linked to a specific cause.25 The risk of certain congenital anomalies can be decreased through preventive public health measures such as vaccination, screening for infections, ensuring adequate dietary intake of vitamins and minerals, and reducing or eliminating exposure to harmful substances (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, pesticides).25

In Canada, approximately 1 in 25 babies, or 400 per 10,000 babies, is diagnosed with one or more congenital anomalies each year.24

Average age of mother at birth of first infant

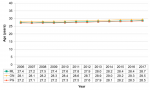

The average age of a mother at the birth of her first infant was 28.7 years in Middlesex-London in 2017, compared to 29.5 years in Ontario. Each year from 2006 to 2017, the average age was significantly lower in Middlesex-London compared to Ontario. The average age of first time mothers in Middlesex-London, Ontario and the Peer Group gradually increased over time from 2006 to 2017 (Fig. 12.1.16).

The average age did not differ significantly between the urban and rural population of Middlesex-London from 2006 to 2017 (figure not shown).

Interpretation:

Pregnancy and childbirth among females who are particularly young (i.e., teenagers) or who are older (i.e., aged 35 and older) tend to be associated with greater odds of complications during pregnancy and delivery.26

Compared to previous generations, more women are now having children at older ages. The trend toward delaying parenthood can be attributed to many factors, including: delayed marriage, effective birth control, waiting to achieve a certain level of financial stability, and the pursuit of higher education and career advancement.27-29 The development of new reproductive technologies and fertility treatments has meant that some women are able to get pregnant at later ages than before.28 However, a woman’s fertility begins to decline in her early to mid thirties30, and increasing maternal age is significantly associated with miscarriages, chromosomal abnormalities, congenital anomalies, gestational diabetes, placenta previa (placenta partially or totally covers the mother’s cervix) and caesarean deliveries (C-section).29

Healthy Growth and Development Guideline, 2018

Ontario Public Health Standards: Requirements for Programs, Services, and Accountability

References:

1. Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. Healthy Growth and Development Guideline, 2018 [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 26]. Available from: http://health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/oph_standards/docs/...

2. Kent MM, Haub C. In (Cautious) Defense of the Crude Birth Rate. Popul Today 1984;12(2):6-7.

3. World Health Organization South-East Asia Regional Office. Sex Ratio [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/health_situation_trends/data/chi/sex-rat...

4. Public Health Agency of Canada. Health Risks of Fertility Treatments [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/fertility/health-risks-f...

5. Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian Perinatal Health Report, 2008 Edition [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: 2008 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Available from: http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/publicat/2008/cphr-rspc/pdf/cphr-rspc08-eng.pdf

6. United Nations Children’s Fund. Low Birthweight [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/nutrition/low-birthweight/

7. World Health Organization. Global Nutrition Targets 2025: Low Birth Weight Policy Brief [Internet]. Geneva: 2014 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Report No.: WHO/NMH/NHD/14.5. Available from: https://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/globaltargets2025_policybrief...

8. United Nations Children’s Fund. Low Birthweight: Country, Regional and Global Estimates [Internet]. New York: UNICEF, 2004 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/publications/files/low_birthweight_from_EY.pdf

9. Belbasis L, Savvidou MD, Kanu C, Evangelou E, Tzoulaki I. Birth Weight in Relation to Health and Disease in Later Life: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. BMC Med [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2019 Apr 25];14(1):147. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0692-5 DOI: 10.1186/s12916-016-0692-5

10. Stanford Children's Health. Low Birthweight [Internet]. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University; 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=low-birthweight-90...

11. Statistics Canada. Table 13-10-0064-01 Birth-Related Indicators (Low and High Birth Weight, Small and Large for Gestational Age, Pre-Term Births), by Sex, Five-Year Period, Canada and Inuit Regions [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310006401

12. Chatfield J. Acog Issues Guidelines on Fetal Macrosomia. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Am Fam Physician [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2018 Nov 8];64(1):169-70. Available from: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2001/0701/p169.html

13. Parsons TJ, Power C, Logan S, Summerbell CD. Childhood Predictors of Adult Obesity: A Systematic Review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord [Internet]. 1999 [cited 2018 Nov 8];23 Suppl 8:S1-107. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/0801139.pdf?origin=ppub

14. Stanford Children's Health. Large for Gestational Age [Internet]. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Children's Health; 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=large-for-gestatio...

15. Storms MR, Van Howe RS. Birthweight by Gestational Age and Sex at a Rural Referral Center. J Perinatol [Internet]. 2004 [cited 2018 Nov 8];24:236. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211065 DOI: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211065

16. Callaghan WM, Dietz PM. Differences in Birth Weight for Gestational Age Distributions According to the Measures Used to Assign Gestational Age. Am J Epidemiol [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2018 Nov 8];171(7):826-36. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/aje/article/171/7/826/86578 DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwp468

17. Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, Joseph KS, Allen A, Abrahamowicz M, et al. A New and Improved Population-Based Canadian Reference for Birth Weight for Gestational Age. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2001 [cited 2018 Nov 8];108(2):e35. Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/108/2/e35.full.pdf DOI: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35

18. Stanford Children's Health. Small for Gestational Age [Internet]. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Children's Health; 2019 [cited 2019 Apr 26]. Available from: https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=small-for-gestatio...

19. Association of Public Health Epidemiologists in Ontario. Vital Statistics Stillbirth Data [Internet]. Ontario: Association of Public Health Epidemiologists in Ontario; 2013 [cited 2019 Apr 26]. Available from: http://core.apheo.ca/index.php?pid=212

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Facts About Stillbirth [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2018 Nov 8]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/stillbirth/facts.html

21. Van den Veyver IB. Recent Advances in Prenatal Genetic Screening and Testing. F1000Res [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2018 Nov 8];5:2591. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/PMC5089140/ DOI: 10.12688/f1000research.9215.1

22. Provincial Council for Maternal and Child Health (PCMCH) and The Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN) Ontario Perinatal Record Working Group. A User Guide to the Ontario Perinatal Record [Internet]. Toronto, ON: Queen's Printer for Ontario, 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 26]. Available from: http://www.pcmch.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/OPR_UserGuide_2018Upda...

23. Joseph KS, Kinniburgh B, Hutcheon JA, Mehrabadi A, Basso M, Davies C, et al. Determinants of Increases in Stillbirth Rates from 2000 to 2010. CMAJ [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2018 Nov 9];185(8):E345-51. Available from: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/185/8/E345.long DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.121372

24. Irvine B, Luo W, León JA. Congenital Anomalies in Canada 2013: A Perinatal Health Surveillance Report by the Public Health Agency of Canada's Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Nov 12];35(1):21-2. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/PMC4939458/

25. World Health Organization. Congenital Anomalies [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2016 [cited 2019 Apr 25]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/congenital-anomalies

26. Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Bommarito K, Madden T, Olsen MA, et al. Maternal Age and Risk of Labor and Delivery Complications. Matern Child Health J [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2018 Nov 8];19(6):1202-11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4418963/ DOI: 10.1007/s10995-014-1624-7

27. Benzies KM. Advanced Maternal Age: Are Decisions About the Timing of Child-Bearing a Failure to Understand the Risks? CMAJ [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2018 Nov 15];178(2):183-4. Available from: http://www.cmaj.ca/content/cmaj/178/2/183.full.pdf DOI: 10.1503/cmaj.071577

28. Canadian Institute for Health Information. In Due Time: Why Maternal Age Matters [Internet]. Ottawa: 2011 [cited 2018 Nov 15]. Available from: https://secure.cihi.ca/free_products/AIB_InDueTime_WhyMaternalAgeMatters...

29. Cleary-Goldman J, Malone FD, Vidaver J, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, et al. Impact of Maternal Age on Obstetric Outcome. Obstet Gynecol [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2018 Nov 15];105(5 Pt 1):983-90. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2005/05000/Impact_of_Mate... DOI: 10.1097/01.aog.0000158118.75532.51

30. The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). Age and Fertility [Internet]. Ottawa, ON: The Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada; 2014 [cited 2019 Apr 26]. Available from: http://pregnancy.sogc.org/fertility-and-reproduction/age-and-fertility/

Last modified on: May 7, 2019

Jargon Explained

Birth rate

The annual number of live births per 1,000 population.

Peer groups

The grouping of Ontario public health units with socio-economic characteristics similar to those of Middlesex-London. It is based on the 2015 Statistics Canada Peer Group A that includes health regions from across Canada that are characterized by having population centres with high population density and a rural mix.

Sex ratio at birth

The ratio of males born alive per 100 females born alive.

Sex of person

Refers to the sex assigned at birth based on a person’s reproductive system and other physical characteristics. A person’s sex may differ from a person’s gender; a person’s gender may change over time and reflects the gender with which a person internally identifies and/or the gender a person publicly expresses.

Multiple live birth rate

The number of multiple live births per 100 live births.

Preterm birth rate

Number of live births delivered before 37 completed weeks of gestation per 100 live births.

Low birth weight rate

The number of live births with a birth weight of less than 2,500 grams, per 100 live births.

High birth weight rate

The number of live births with a birth weight of 4,500 grams or more, per 100 live births.

Small-for-gestational-age rate

The number of live births with a birth weight below the tenth percentile of birth weights for their gestational age and sex, per 100 live births.

Large-for-gestational-age rate

The number of live births with a birth weight above the ninetieth percentile of birth weights for their gestational age and sex, per 100 live births.

Stillbirth rate

The number of births that are stillborn per 1,000 births (live or still).

Congenital anomalies

Abnormalities that are present at birth. They are also known as birth defects or congenital malformations.